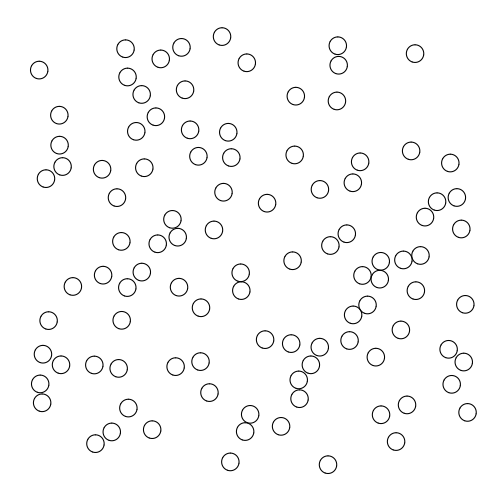

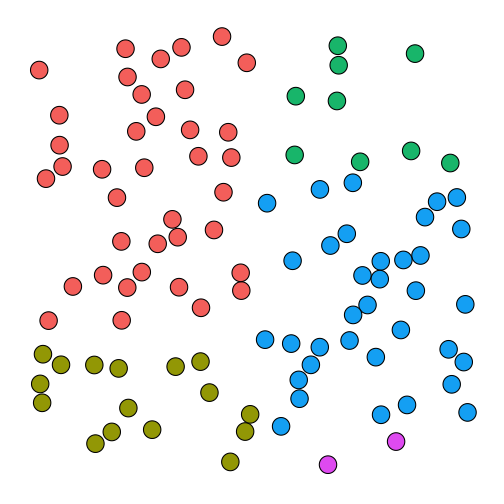

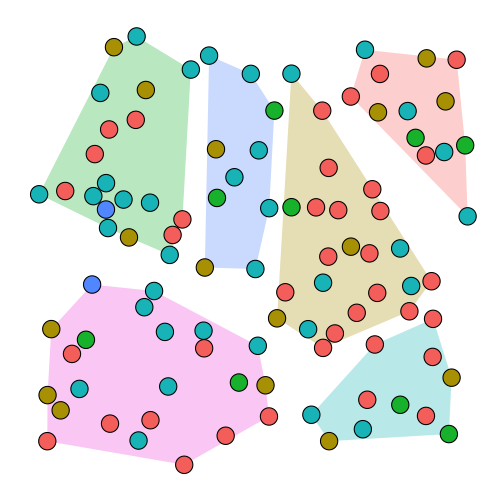

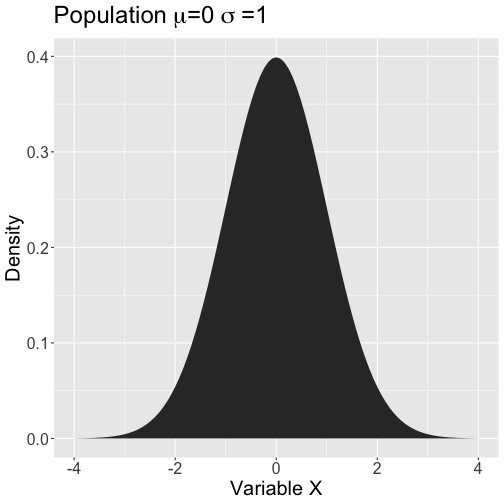

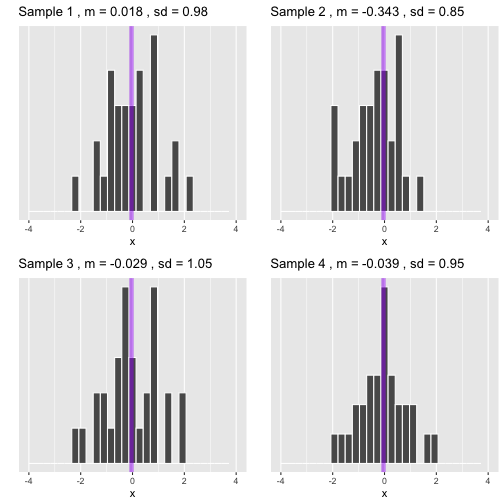

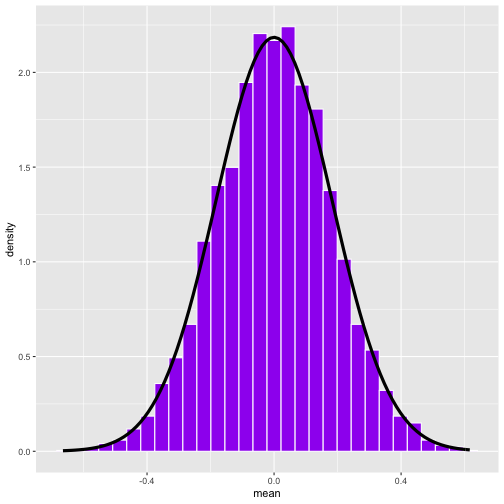

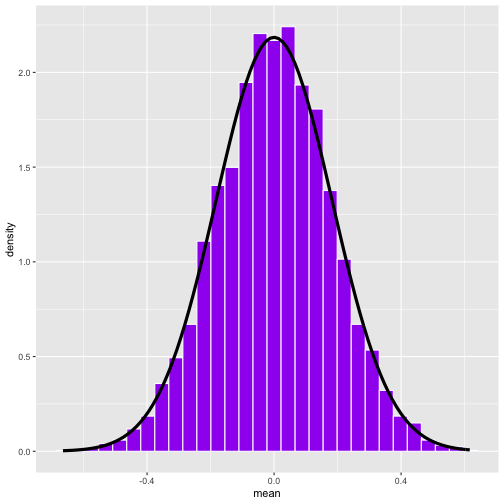

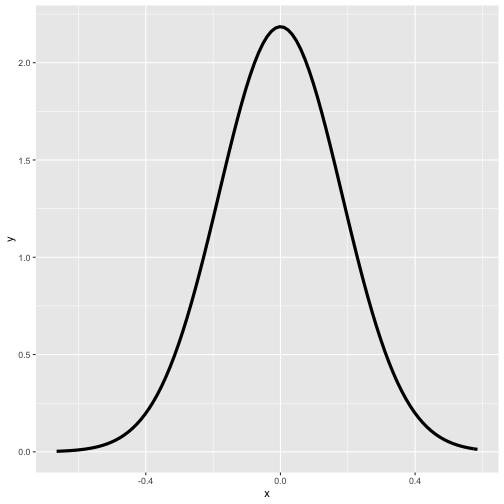

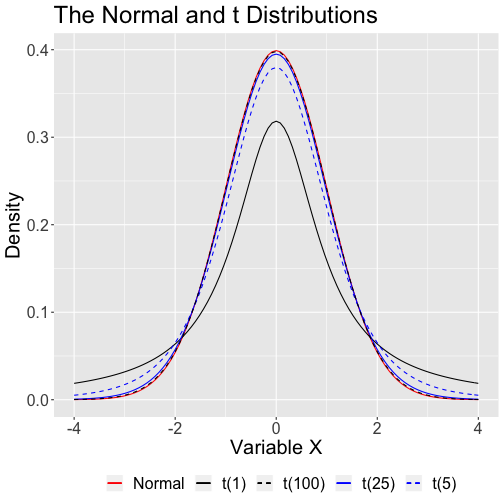

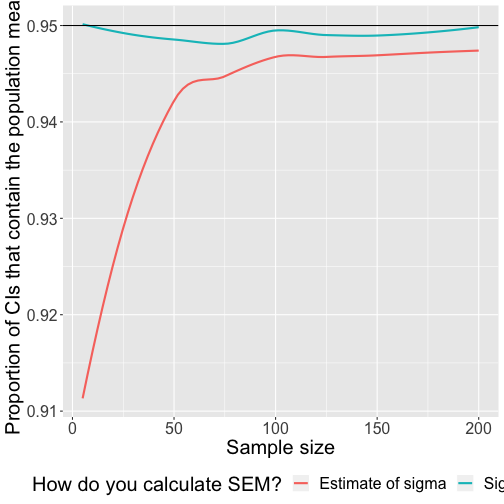

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Sampling --- ### `\(\chi^2\)` redo The sample variance is defined as: `$$s^2 = \frac{\sum_{i = 1}^{N}(X_i-\bar{X})^2}{N-1}$$` We want to find a probability distribution that we can use to estimate likelihoods of given sample variances, given a known population variance. -- Luckily, we note that the formula for `\(s^2\)` can be rearranged: `$$(N-1)s^2 = \sum_{i = 1}^{N}(X_i-\bar{X})^2$$` --- `$$(N-1)s^2 = \sum_{i = 1}^{N}(X_i-\bar{X})^2$$` -- Even better, we can multiply both sides by a constant, `\(\frac{1}{\sigma^2}\)`: `$$\frac{(N-1)s^2}{\sigma^2} = \sum_{i = 1}^{N}\frac{(X_i-\bar{X})^2}{\sigma^2}$$` -- And now another simplication arises: `$$\frac{(N-1)s^2}{\sigma^2} = \sum_{i = 1}^{N}(\frac{(X_i-\bar{X})}{\sigma})^2 = \sum_{i = 1}^{N}Z^2$$` -- What fortune! At turns out, `$$\sum_{i = 1}^{N}Z^2 = \chi^2_N$$` --- ### Why does adding N `\(\chi^2\)` distributions create a normal? Because we assume the `\(\chi^2\)` distributions are independent of one another. - Meaning, whatever value is drawn from the first `\(\chi^2\)` distribution has no effect on what is drawn from the others. This is different from the procedure where we square Z values to get `\(\chi^2\)` - In this case, each original `\(Z\)` value is exactly linked to a specific `\(Z^2\)` value --- To this point, we have assumed that features of the population -- the parameters -- are known. That is rarely the case. The major goal that we have in statistical inference is to make confident claims about the population based on a small representation of it, the sample. Our confidence in the sample as a representation of the population relies on sampling theory. --- ## Terms **Sample**: The particular units from a population on which measures are collected (the data). **Population**: The complete set of units (e.g., people, countries, etc.) from which a sample is selected. **Sampling method**: The procedure used to create a sample. --- Ideally we would like to believe that there is nothing special about a sample. Any other sample from the same population should be *interchangeable* with the one we have in hand. Any sample should be able to “stand for” or be a good proxy for the population. -- Interchangeable or **representative** samples allow us to make confident claims about the population. Samples are **representative** to the extent the population is clearly defined and the sample is selected using an appropriate sampling method. --- **Probability sampling methods** maintain a defensible link between a sample and population. This link is based on statistical theory and rules of probability. **Nonprobability sampling methods** provide only a weak link between a sample and population. This link is based on appeals to common sense and reason. Maybe only blind faith. Despite the clear distinction, it is not unusual for researchers to use a nonprobability sampling method and then draw inferences in a way that implies a strong link from the sample to some population. --- Probability sampling methods have the following simple features: - Define the population so that all population units can be identified (i.e., become candidates for selection). - Select a sample from among those units using a random selection method. --- Common random sampling methods: - **Simple** random sampling: Each of the units in the population has an equal chance of being selected. - **Stratified** random sampling: Identify nonoverlapping strata and carry out simple random sampling within each strata. - **Cluster** random sampling: Divide the population into nonoverlapping clusters. Randomly select clusters and use all of the units within the selected clusters. - **Multistage** random sampling: A combination of the other random sampling methods (stratified random sampling within clusters). ??? In stratified random sampling, the sample sizes within strata can be defined to maintain proportionality or not. Additional concern: with replacement or without replacement --- ### Simple random sampling .left-column[ .small[ In **simple random sampling**, each object would have an equal probability of being selected (1/100). For simple random sampling, any object characteristics (e.g., color) are irrelevant. ] ] <!-- --> --- ### Stratified random sampling .left-column[ .small[ In **stratified random sampling**, the objects are first categorized into strata (e.g., color) and random sampling occurs within strata. The probability of being selected depends on the size of the strata (1/38 in the red strata; 1/2 in the purple strata). ] ] <!-- --> --- ### Cluster Random Sampling .left-column[ .small[ In **cluster random sampling**, clusters of units are selected at random and then all of the units within the chosen clusters are part of the sample. The probability of a particular unit being sampled is a function of the number of clusters. ] ] <!-- --> --- No matter what probability method we use, we know the probability that a unit from the population will be selected. This allows us to determine the **sampling error** so that we can know how well the sample represents the population. Any sample will be off the mark in how well it captures the important features of the population. With probability sampling methods we can estimate how far off the mark we are likely to be. ??? The sampling error is the difference between a sample statistic used to estimate a population parameter and the actual but unknown value of the parameter --- ##Nonprobability sampling methods **Nonprobability sampling methods** select the sample on some basis other than a random process. As a consequence, how well the sample represents the population can be difficult to know and the argument depends on common sense and appeals to reason. These methods include: - Convenience sampling - Purposive sampling - Modal instance sampling - Expert sampling - Quota sampling - Heterogeneity sampling - Snowball sampling ??? Purposive -- selection based on chracteristics (e.g., trying to maximize heterogeneity, experts). *Example: Terman study* Modal -- most typical members. *Example: typical voters* snowball -- members of the study help you recruit additional members. (pyramid scheme sampling?). Useful for hard to reach populations (sex workers, members of support groups) --- The strength of probability sampling methods is that the representativeness of a sample can be known with precision. Probability sampling methods, however, are often quite costly. Under what circumstances are we safe in generalizing from a sample to a population if a nonprobability method was used (e.g., convenience sampling)? We need to give this careful consideration because statistical inference, strictly speaking, assumes random sampling from a clearly defined population. How is random sampling different from random assignment? In what sense are they alike (besides the “random” part)? --- We use features of the sample (*statistics*) to inform us about features of the population (*parameters*). The quality of this information goes up as sample size goes up -- **the Law of Large Numbers**. The quality of this information is easier to defend with random samples. All sample statistics are wrong (they do not match the population parameters exactly) but they become more useful (better matches) as sample size increases. An important practical question is “how big does the sample need to be?” Stated another way, “for a given sample size, how precise is a sample statistic as a representation of the population?” -- The sampling distribution provides the answers. --- .left-column[ ### Population distribution .small[The parameters of this distribution are unknown. We use the sample to inform us about the likely characteristics of the population.] ] <!-- --> --- .left-column[ ###Samples from the population. .small[ Each sample distribution will resemble the population. That resemblance will be better as sample size increases: The Law of Large Numbers. Statistics (e.g., mean) can be calculated for any sample. ] ] <!-- --> --- .left-column[ .small[ The statistics from a large number of samples also have a distribution: the **sampling distribution**. By the **Central Limit Theorem**, this distribution will be normal as sample size increases. This distribution has a standard deviation, called the **standard error of the mean**. *Its mean converges on `\(\mu\)`.* ] ] <!-- --> ??? Sampling distributions can be constructed around any statistic -- ranges, standard deviations, difference scores. The standard errors of those distributions are also standard errors. (E.g., the standard error of the difference.) --- [The most exciting Excel spreadsheet ever](../demo/Sampling Demo.xlsm) Made by Geoff Cumming * Be sure to enable macros. --- .left-column[ .small[ We don’t actually have to take a large number of random samples to construct the sampling distribution. It is a theoretical result of the Central Limit Theorem. We just need an estimate of the population parameter, s, which we can get from the sample. ] ] <!-- --> --- .left-column[ .small[ We don’t actually have to take a large number of random samples to construct the sampling distribution. It is a theoretical result of the Central Limit Theorem. We just need an estimate of the population parameter, s, which we can get from the sample. ] ] <!-- --> --- The sampling distribution of means can be used to make probabilistic statements about means in the same way that the standard normal distribution is used to make probabilistic statements about scores. For example, we can determine the range within which the population mean is likely to be with a particular level of confidence. Or, we can propose different values for the population mean and ask how typical or rare the sample mean would be if that population value were true. We can then compare the plausibility of different such “models” of the population. --- The key is that we have a sampling distribution of the mean with a standard deviation **(the SEM)** that is linked to the population: `$$SEM = \sigma_M = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{N}}$$` We do not know `\(\sigma\)` but we can estimate it based on the sample statistic: `$$\hat{\sigma} = s = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N-1}\sum_{i=1}^N(X-\bar{X})^2}$$` --- `$$\hat{\sigma} = s = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N-1}\sum_{i=1}^N(X-\bar{X})^2}$$` This is the sample estimate of the population standard deviation. This is an unbiased estimate of `\(\sigma\)` and relies on the sample mean, which is an unbiased estimate of `\(\mu\)`. This is different from the sample standard deviation, which divides the sum of squares by `\(N\)` rather than `\(N-1\)`. `$$SEM = \sigma_M = \frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}} = \frac{\text{Estimate of pop SD}}{\sqrt{N}}$$` (Most methods of calculating standard deviation assume you're estimating the popluation `\(\sigma\)` from a sample and correct for bias.) --- The sampling distribution of the mean has variability, represented by the SEM, reflecting uncertainty in the sample mean as an estimate of the population mean. The assumption of normality allows us to construct an interval within which we have good reason to believe a sample mean will fall if it comes from a particular population: $$\mu - (1.96\times SEM) \leq \bar{X} \leq \mu + (1.96\times SEM) $$ We can reorganize this to allow statements about the population mean, which is usually not known: $$\bar{X} - (1.96\times SEM) \leq \mu \leq \bar{X} + (1.96\times SEM) $$ --- $$\bar{X} - (1.96\times SEM) \leq \mu \leq \bar{X} + (1.96\times SEM) $$ This is referred to as the **95% confidence interval (CI)**. Note the assumption of normality, which should hold by the Central Limit Theorem, if N is sufficiently large. The 95% CI is sometimes represented as: `$$CI_{95} = \bar{X} \pm [1.96\frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}}]$$` --- .left-column[ .small[ What if N is not “sufficiently large?” The normal distribution assumes we know the population mean and standard deviation. But we don’t. We only know the sample mean and standard deviation, and those have some uncertainty about them. That uncertainty is reduced with large samples, so that the normal is “close enough.” In small samples, the t distribution provides a better approximation. ] ] <!-- --> --- For small samples, we need to use the t distribution with its fatter tails. This produces wider confidence intervals—the penalty we have to pay for our ignorance about the population. The form of the confidence interval remains the same. We simply substitute a corresponding value from the t distribution (using df = `\(N -1\)`). `$$CI_{95} = \bar{X} \pm [1.96\frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}}]$$` `$$CI_{95} = \bar{X} \pm [Z_{.975}\frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}}]$$` `$$CI_{95} = \bar{X} \pm [t_{.975, df = N-1}\frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}}]$$` --- The meaning of the confidence interval can be a bit confusing and arises from the peculiar language forced on us by the frequentist viewpoint. The CI DOES NOT mean “there is a 95% probability that the true mean lies inside the confidence interval.” It means that if we carried out random sampling from the population a large number of times, and calculated the 95% confidence interval each time, then 95% of those intervals can be expected to contain the population mean. (Ugh, maybe those smug Bayesians are on to something.) Maybe less tortured: We have good reason to believe the true mean lies in this interval because 95% of the time such intervals contain the true mean. - And even that interpretation is problematic, because it assumes our estimate of the standard deviation is error-free. ??? As Hays (1988) notes, the confidence limits based on the sample estimate of the population standard deviation are approximately correct, especially as sample size increases. They are approximately correct because there is uncertainty in the calculation of the SEM based on the sample estimate of the standard deviation. --- .left-column[ .small[ ###Simulation At each sample size, draw 5000 samples from known population ( `\(\mu = 0\)` , `\(\sigma = 1\)` ). Calculate CI for each sample using `\(s\)` and record whether or not 0 was in that interval. Calculate CI using for each sample using `\(\sigma\)`. ] ] <!-- --> --- In the past, my classroom exams (aggregating over many classes) have a mean of 90 and a standard deviation of 8. My next class will have 100 students. What range of exam means would be plausible if this class is similar to past classes (comes from the same population)? ```r M = 90 SD = 8 N = 100 sem = SD/sqrt(N) ci_lb_z = M - sem * qnorm(p = .975) ci_ub_z = M + sem * qnorm(p = .975) print(c(ci_lb_z, ci_ub_z)) ``` ``` ## [1] 88.43203 91.56797 ``` ```r ci_lb_z = M - sem * qt(p = .975, df = N-1) ci_ub_z = M + sem * qt(p = .975, df = N-1) print(c(ci_lb_z, ci_ub_z)) ``` ``` ## [1] 88.41263 91.58737 ``` --- I give a classroom exam that produces a mean of 83.4 and a standard deviation of 10.6. A total of 26 students took the exam. What is the 95% confidence interval around the mean? What kinds of population inferences can I draw? ```r M = 83.4 SD = 10.6 N = 26 sem = SD/sqrt(N) ci_lb_z = M - sem * qnorm(p = .975) ci_ub_z = M + sem * qnorm(p = .975) print(c(ci_lb_z, ci_ub_z)) ``` ``` ## [1] 79.32557 87.47443 ``` ```r ci_lb_z = M - sem * qt(p = .975, df = N-1) ci_ub_z = M + sem * qt(p = .975, df = N-1) print(c(ci_lb_z, ci_ub_z)) ``` ``` ## [1] 79.11857 87.68143 ``` --- class:inverse ## Next time... Null Hypothesis Significance Testing