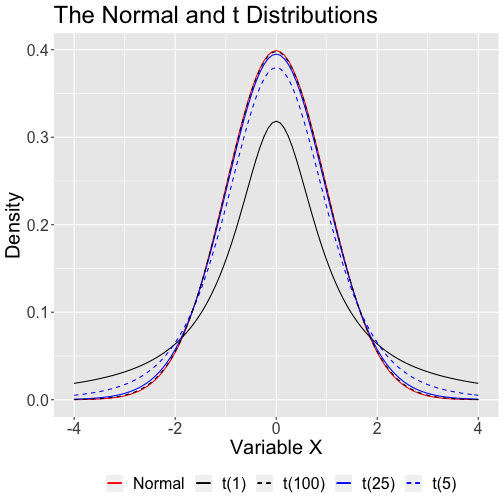

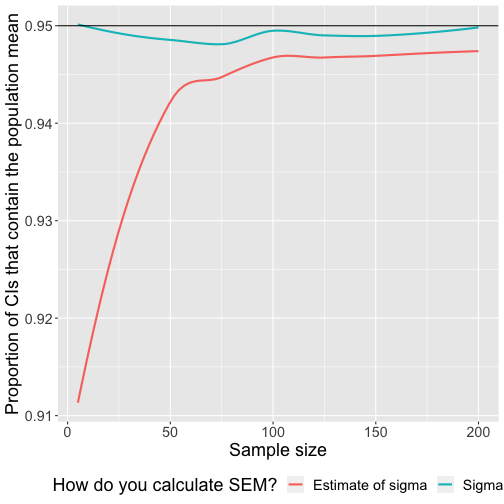

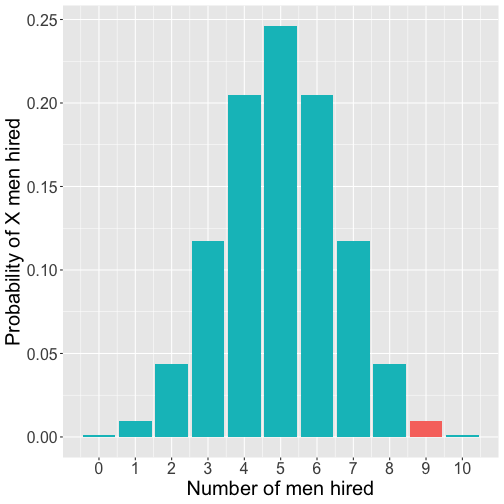

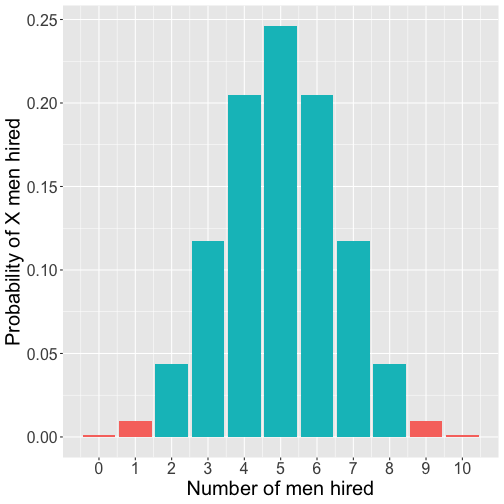

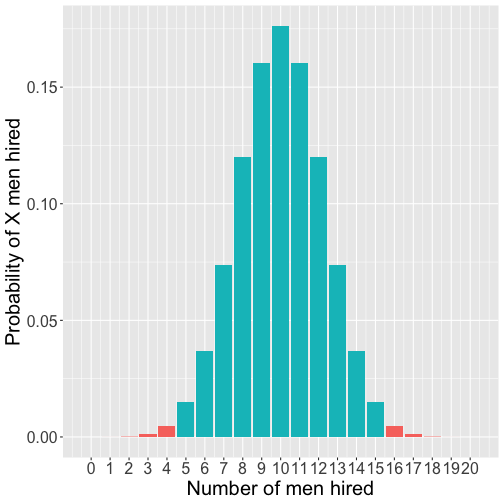

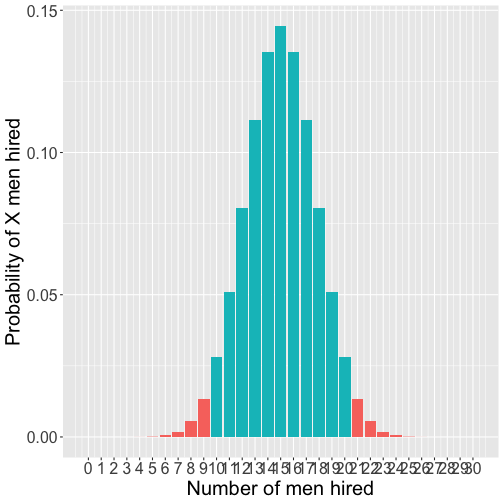

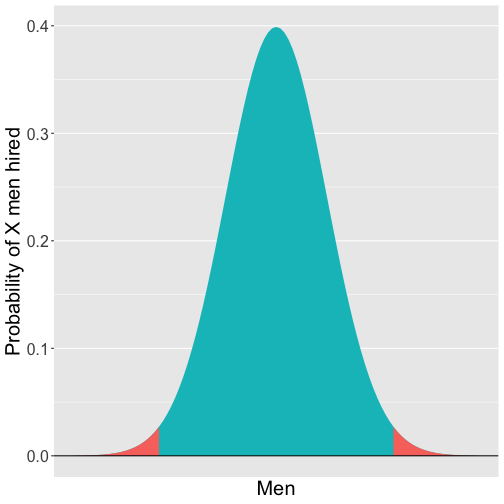

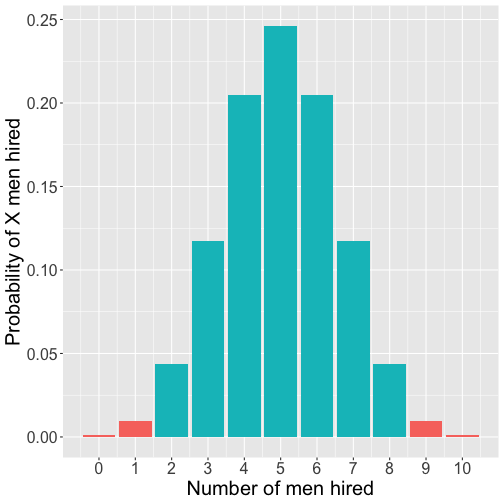

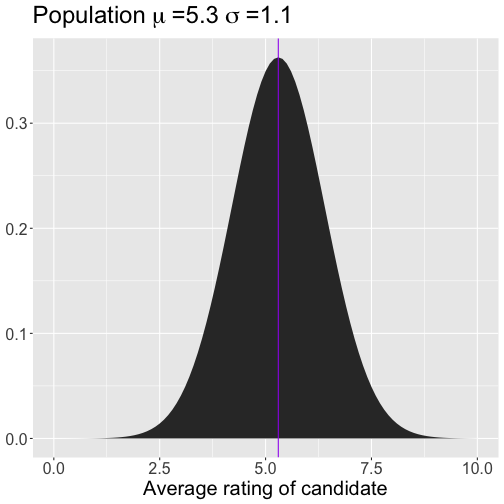

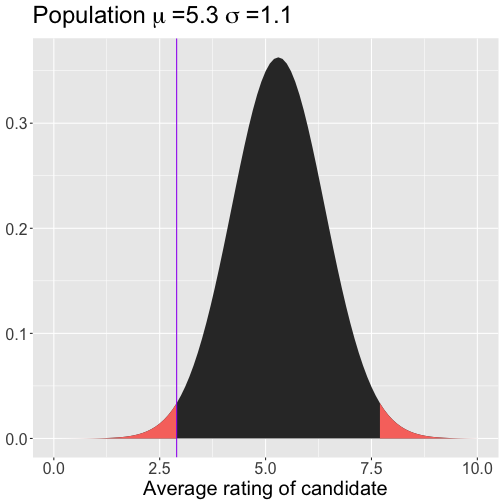

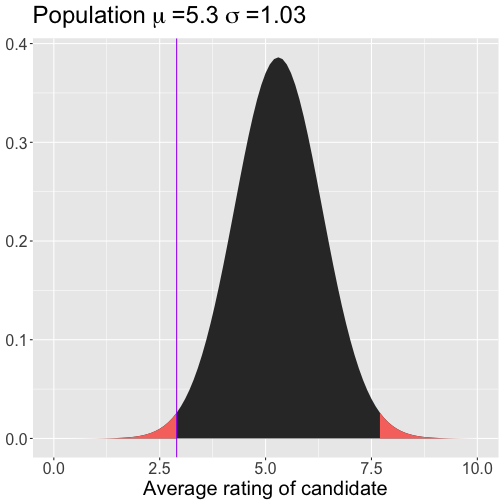

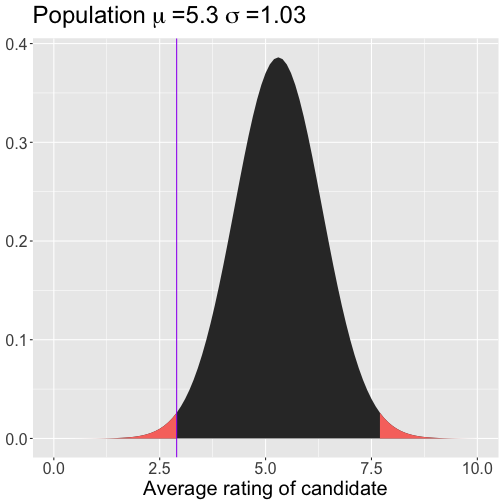

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Hypothesis testing (NHST) --- Representative sampling is important! Check out [this episode of the FiveThrityEight Politics Podcast](https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/politics-podcast-how-the-media-projects-the-winner-of-an-election/). --- ## Last time... Sampling! - Importance of random samples - Sampling distributions - Inferring population mean from sample mean - Confidence intervals --- $$\bar{X} - (1.96\times SEM) \leq \mu \leq \bar{X} + (1.96\times SEM) $$ This is referred to as the **95% confidence interval (CI)**. Note the assumption of normality, which should hold by the Central Limit Theorem, if N is sufficiently large. The 95% CI is sometimes represented as: `$$CI_{95} = \bar{X} \pm [1.96\frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}}]$$` --- .left-column[ .small[ What if N is not “sufficiently large?” The normal distribution assumes we know the population mean and standard deviation. But we don’t. We only know the sample mean and standard deviation, and those have some uncertainty about them. That uncertainty is reduced with large samples, so that the normal is “close enough.” In small samples, the t distribution provides a better approximation. ] ] <!-- --> --- For small samples, we need to use the t distribution with its fatter tails. This produces wider confidence intervals—the penalty we have to pay for our ignorance about the population. The form of the confidence interval remains the same. We simply substitute a corresponding value from the t distribution (using df = `\(N -1\)`). `$$CI_{95} = \bar{X} \pm [1.96\frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}}]$$` `$$CI_{95} = \bar{X} \pm [Z_{.975}\frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}}]$$` `$$CI_{95} = \bar{X} \pm [t_{.975, df = N-1}\frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}}]$$` --- The meaning of the confidence interval can be a bit confusing and arises from the peculiar language forced on us by the frequentist viewpoint. The CI DOES NOT mean “there is a 95% probability that the true mean lies inside the confidence interval.” It means that if we carried out random sampling from the population a large number of times, and calculated the 95% confidence interval each time, then 95% of those intervals can be expected to contain the population mean. (Ugh, maybe those smug Bayesians are on to something.) Maybe less tortured: We have good reason to believe the true mean lies in this interval because 95% of the time such intervals contain the true mean. - And even that interpretation is problematic, because it assumes our estimate of the standard deviation is error-free. ??? As Hays (1988) notes, the confidence limits based on the sample estimate of the population standard deviation are approximately correct, especially as sample size increases. They are approximately correct because there is uncertainty in the calculation of the SEM based on the sample estimate of the standard deviation. --- .left-column[ .small[ ###Simulation At each sample size, draw 5000 samples from known population ( `\(\mu = 0\)` , `\(\sigma = 1\)` ). Calculate CI for each sample using `\(s\)` and record whether or not 0 was in that interval. Calculate CI using for each sample using `\(\sigma\)`. ] ] <!-- --> --- In the past, my classroom exams (aggregating over many classes) have a mean of 90 and a standard deviation of 8. My next class will have 100 students. What range of exam means would be plausible if this class is similar to past classes (comes from the same population)? ```r M = 90 SD = 8 N = 100 sem = SD/sqrt(N) ci_lb_z = M - sem * qnorm(p = .975) ci_ub_z = M + sem * qnorm(p = .975) print(c(ci_lb_z, ci_ub_z)) ``` ``` ## [1] 88.43203 91.56797 ``` ```r ci_lb_z = M - sem * qt(p = .975, df = N-1) ci_ub_z = M + sem * qt(p = .975, df = N-1) print(c(ci_lb_z, ci_ub_z)) ``` ``` ## [1] 88.41263 91.58737 ``` --- I give a classroom exam that produces a mean of 83.4 and a standard deviation of 10.6. A total of 26 students took the exam. What is the 95% confidence interval around the mean? What kinds of population inferences can I draw? ```r M = 83.4 SD = 10.6 N = 26 sem = SD/sqrt(N) ci_lb_z = M - sem * qnorm(p = .975) ci_ub_z = M + sem * qnorm(p = .975) print(c(ci_lb_z, ci_ub_z)) ``` ``` ## [1] 79.32557 87.47443 ``` ```r ci_lb_z = M - sem * qt(p = .975, df = N-1) ci_ub_z = M + sem * qt(p = .975, df = N-1) print(c(ci_lb_z, ci_ub_z)) ``` ``` ## [1] 79.11857 87.68143 ``` --- ## Why do we divide by `\(\sqrt{N}\)` `$$\sigma^2_M = E(\bar{x}^2)-(E(x))^2$$` `$$\bar{x}^2 = (\frac{\sum{x}}{N})^2$$` `$$\bar{x}^2 = \frac{1}{N^2}(x^2_1+x^2_2+\dots+x^2_N+2\sum{x_ix_j})$$` `$$E(\bar{x}^2) = \frac{1}{N^2}(E(x^2_1)+E(x^2_2)+\dots+E(x^2_N)+2\sum{E(x_ix_j)})$$` `$$\sigma^2_X = E(X^2)-(E(X))^2$$` `$$\sigma^2_X = E(X^2)-\mu^2$$` `$$\sigma^2_X+\mu^2 = E(X^2)$$` --- `$$E(\bar{x}^2) = \frac{1}{N^2}((\sigma^2_X+\mu^2)+(\sigma^2_X+\mu^2)+\dots+(\sigma^2_X+\mu^2)+2\sum{E(x_ix_j)})$$` `$$E(\bar{x}^2) = \frac{1}{N^2}(N(\sigma^2_X+\mu^2)+2\sum{E(x_ix_j)})$$` `$$E(x_ix_j) = E(x_i)E(x_j) = \mu\mu=\mu^2$$` `$$E(\bar{x}^2) = \frac{1}{N^2}(N(\sigma^2_X+\mu^2)+2\sum{(\mu^2)})$$` `$$E(\bar{x}^2) = \frac{1}{N^2}(N(\sigma^2_X+\mu^2)+2\frac{N(N-1)}{2}\mu^2)$$` --- `$$E(\bar{x}^2) = \frac{1}{N^2}(N(\sigma^2_X+\mu^2)+N(N-1)\mu^2)$$` `$$E(\bar{x}^2) = \frac{1}{N}(\sigma^2_X+\mu^2+(N-1)\mu^2)$$` `$$E(\bar{x}^2) = \frac{1}{N}(\sigma^2_X+N\mu^2)$$` `$$E(\bar{x}^2) = \frac{\sigma^2_X}{N}+\mu^2$$` --- `$$\sigma^2_M = E(\bar{x}^2)-(E(x))^2$$` `$$E(\bar{x}^2) = \frac{\sigma^2_X}{N}+\mu^2$$` `$$\sigma^2_M = \frac{\sigma^2_X}{N} + \mu^2-\mu^2$$` `$$\sigma^2_M = \frac{\sigma^2_X}{N}$$` `$$\sqrt{\sigma^2_M} = \sqrt{\frac{\sigma^2_X}{N}} = \frac{\sigma_X}{\sqrt{N}}$$` --- class: inverse ## Hypothesis What is a hypothesis? -- In statistics, a **hypothesis** is a statement about the population. It is usually a prediction that a parameter describing some characteristic of a variable takes a particular numerical value, or falls into a certain range of values. For example, I might hypothesize that that given equal qualifications, male candidates are viewed more favorably and more likely to be hired than female candidates (Moss-Rascusin et al., PNAS, 2012). We would call this a **research hypothesis.** This could be represented numerically as, as a **statistical hypothesis**: `$$\text{Proportion}_{\text{Male applicants hired}} > \text{Proportion}_{\text{Females applicants hired}}$$` --- ## The null hypothesis In Null Hypothesis Significance Testing, we... test a null hypothesis. A **null hypothesis** ( `\(H_0\)` ) is a statement of no effect. The *research hypothesis* states that there is no relationship between X and Y, or our intervention has no effect on the outcome. - The *statistical hypothesis* is either that the population parameter is a single value, like 0, or that a range, like 0 or smaller. --- ## The alternative hypothesis According to probability theory, our sample space must cover all possible elementary events. Therefore, we create an **alternative hypothesis** ( `\(H_1\)` ) that is every possible event not represented by our null hypothesis. .pull-left[ `$$H_0: \mu = 4$$` `$$H_1: \mu \neq 4$$` ] -- .pull-right[ `$$H_0: \mu \leq -4$$` `$$H_1: \mu > -4$$` ] --- ## The tortured logic of NHST We create two hypotheses, `\(H_0\)` and `\(H_1\)`. Usually, we care about `\(H_1\)`, not `\(H_0\)`. In fact, what we really want to know is how likely `\(H_1\)`, given our data. `$$P(H_1|D)$$` Instead, we're going to test our null hypothesis. Well, not really. We're going to assume our null hypothesis is true, and test how likely we would be to get these data. `$$P(D|H_0)$$` --- ## Example #1 Consider the example of possible gender discrimination in hiring a research technician at University X. Let `\(\Pi\)` be the probability any particular selection is male. University X claims that `\(\Pi = .5\)`. This can be the null hypothesis for two reasons: 1. If this is true, than an equal number of men and women** would be hired, and there would be no bias. 2. Regardless of whether this matches the population, this is the University's claim and we want to test it. --- ## Example #1 As a critical and suspicious graduate student who is well informed about unconscious bias in STEM, you’re skeptical that there is no gender bias in hiring, and you have an alternative hypothesis that the probability of men being hired is greater than .5. `$$H_0: \Pi = .5$$` `$$H_1: \Pi \neq .5$$` --- ## Example #1 To test the null hypothesis, you look at the hiring practices of University X over the last year, and find that they had 10 job openings, for which they hired 9 men. The question you're going to ask is: - "How likely is it that 9 out of 10 hires were men, if the probability of hiring a man is .5?" This is the essence of NHST. -- You can already test this using what you know about the binomial distribution. --- ```r dbinom(9, size = 10, prob = .5) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.009765625 ``` <!-- --> --- ## Complications with the binomial The likelihood of hiring a man 9 times out of 10 *if the true probability of hiring a man is .5* is 0.01. That's pretty low! That's so low that we might begin to suspect that the true probability is not .5. But there's a problem with this example. Sometimes University X has 10 job openings, but sometimes it has 1 and sometimes it has 30, and on and on. The binomial doesn't really apply to University X's hiring practices because N can change (and it's an assumption of the binomial that we know N). What we really want is not to assess 9 out of 10 times, but a proportion, like .9. How many different proportions could result year to year? --- ## Our statistic is usually continuous When we estimate a statistic for our sample -- like the proportion of males hired, or the average IQ score, or the relationship between age in months and second attending to a new object -- that statistic is nearly always continuous. So we have to assess the probability of that statistic using a probability distribution for continuous variables, like the normal distribution. (Or t, or F, or `\(\chi^2\)` ). What is the probability of any value in a continuous distribution? --- .left-column[ .small[ Instead of calculating the probability of our statistic, we calculate the probability of our statistic *or more extreme* under the null. The probability of hiring 9 men out of 10 or more extreme is 0.02.] ] <!-- --> --- .left-column[ .small[ As we have more trials... ] ] <!-- --> --- .left-column[ .small[ ... and more trials... ] ] <!-- --> --- .left-column[ .small[ If our measure was continuous, it would look something like this.] ] <!-- --> --- ## Quick recap ### For any NHST test, we: 1. Identify the null hypothesis ( `\(H_0\)` ), which is usually the opposite of what we think to be true. 2. Collect data. 3. Determine how likely we are to get these data or more extreme if the null is true. -- ### What's missing? 4. How do we determine what the distribution looks like if the null hypothesis is true? 5. How unlikely do the data have to be to "reject" the null? --- ## Enter sampling distributions .pull-left[ <!-- --> ] .pull-right[ When we were analyzing the gender problem, we built the distribution under the null using the binomial. This is our **sampling distribution.** What do we need to know to build a sampling distribution based on the binomial? ] --- But as we said before, we're not really going to use the binomial much to make inferences about statistics, because the vast majority of our statistics are continuous, not discrete. Instead, we'll use other distributions to create our sampling distributions. Sometimes `\(t\)` , or `\(F\)` , or `\(\chi^2\)` . For now, we'll work through an example using the standard normal distribution. --- ## Example #2 University X has been around for 150 years, and so has 150 years worth of ratings of male applicants. You dig through all the old university files and calculate the average rating of male applicants (5.3 out of 10) and also the standard deviation of those ratings (3.3). You then collect the ratings of 9 female applicants in 2018 and calculate their average rating (2.9) and also the standard deviation of their rating (3.1) How do you generate the sampling distribution around the null? ??? Null: distribution of men's scores -- you know this population, trying to see if ratings of female applicants come from the same distribution of scores --- .left-column[ .small[ The mean of the sampling distribution = the mean of the null hypothesis The standard deviation of the sampling distribution: `$$SEM = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{N}}$$` ] ] <!-- --> ??? ##What must we assume in order to use the SEM? Random sampling --- .left-column[ .small[ The mean of the sampling distribution = the mean of the null hypothesis The standard deviation of the sampling distribution: `$$SEM = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{N}}$$` ] ] <!-- --> ??? Calculate SEM on board. `\(\sigma = 3.3\)` `\(N = 9\)` --- All well and good. But rarely will you have access to all the data in your population, so you won't be able to calculate the standard deviation. What will you do? -- `$$SEM = \frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}} = \frac{s}{\sqrt{N}}$$` So long as your estimate of the standard deviation is already corrected for bias (you've divided by `\(N-1\)` ), then you can swap in your sample SD. --- .left-column[ .small[ If you didn't know the population (male's) standard deviation, you would use the sample of females to estimate the population standard deviation. `$$SEM = \frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}}$$`] ] <!-- --> ??? Calculate SEM on board. `\(\hat{\sigma} = 3.1\)` `\(N = 9\)` --- .pull-left[ <!-- --> ] .pull-right[ We have a normal distribution for which we know the mean (M), the standard deviation (SEM), and a score of interest ( `\(\bar{X}\)` ). We can use this information to calculate a Z-score; in the context of comparing one mean to a sampling distribution of means, we call this a **Z-statistic**. ] `$$Z = \frac{\bar{X}- M}{SEM} = \frac{2.9-5.3}{1.03} = -2.32$$` --- `$$Z = \frac{\bar{X}- M}{SEM} = \frac{2.9-5.3}{1.03} = -2.32$$` And here's where we use the properties of the Standard Normal Distribution to calculate probabilities, specifically the probability of getting a score this far away from `\(\mu\)` or more extreme: ```r pnorm(-2.32) + pnorm(2.32, lower.tail = F) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.02034088 ``` ```r pnorm(-2.32)*2 ``` ``` ## [1] 0.02034088 ``` The probability that the average female applicant's score would be at least 2.4 units away from the average male score is 0.02. --- The probability that the average female applicant's score would be at least 2.4 units away from the average male score is 0.02. 0.02 is our p-value. What does this mean? -- ### A p-value DOES NOT: - Tell you that the probability that the null hypothesis is true. - Prove that the alternative hypothesis is true. - Tell you anything about the size or magnitude of any observed difference in your data. --- `$$p = 0.02$$` Is that a really low probability? -- Before you test your hypotheses -- ideally, even before you collect the data -- you have to determine how low is too low. Researchers set an alpha ( `\(\alpha\)` ) level that is the probability at which you declare your result to be "statistically significant." How do we determine this? -- Consider what the p-value means. In a world where the null ( `\(H_0\)` ) is true, then by chance, we'll get statistics in the extreme. Specifically, we'll get them `\(\alpha\)` proportion of the time. So `\(\alpha\)` is our tolerance for False Positives or incorrectly rejecting the null. --- Historically, psychologists have chosen to set their `\(\alpha\)` level at .05, meaning any p-value less than .05 is considered "statistically significant" or the null is rejected. This means that, among the times we examine a relationship that is truly null, we will reject the null 1 in 20 times. Some have argued that this is not conservative enough and we should use `\(\alpha < .005\)` ([Benjamin et al., 2018](../readings/Benjamin_etal_2018.pdf)). --- ## NHST Steps 1. Define `\(H_0\)` and `\(H_1\)`. 2. Choose your `\(\alpha\)` level. 3. Collect data. 4. Define your sampling distribution using your null hypothesis and either the knowns about the population or estimates of the population from your sample. 5. Calculate the probability of your data or more extreme under the null. (To get the probability, you'll need to calculate some kind of standardized score, like a z-statistic.) 6. Compare your probability (p-value) to your `\(\alpha\)` level and decide whether your data are "statistically significant" (reject the null) or not (retain the null). --- class: inverse ## Next time... .small[more NHST] .center[ <img src="images/halloween.jpeg" width="60%" /> ] ??? next week office hours....