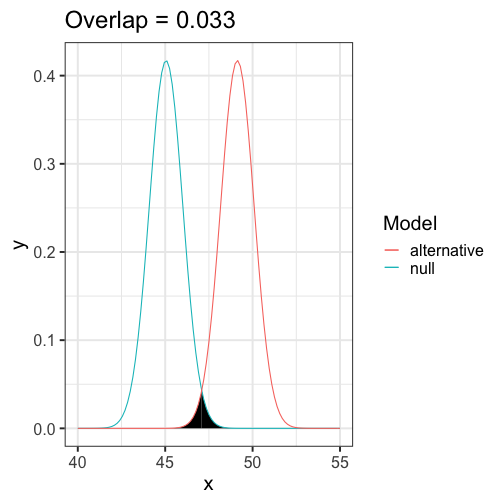

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # One-sample hypothesis tests --- ## Last time... * Chi-square `\((\chi^2)\)` tests * Goodness of fit * Independence -- `$$\chi^2_{df} = \sum\frac{(O-E)^2}{E}$$` `$$\chi^2_{df} = \frac{\text{Signal}}{\text{Noise}}$$` --- ### Example Nate Silver is examining data from the 2020 election in an effort to improve his prediction models. He suspects that there may be a relationship between being a red county (the majority voting for the Republican candidate) and being a rural county. He looks at the contingency table of these two variables: | | Urban | Rural | Row Total | |--------------|:-----:|:-----:|:---------:| | Red | 731 | 492 | 1223 | | Blue | 1708 | 210 | 1918 | | Column total | 2439 | 702 | 3141 | What statistical test will Nate use to analyze his data? --- Step 1. Define null and alternative hypothesis. * `\(H_0\)`: Being rural county is independent of being a red county. (No relationship) * `\(H_A\)`: Being rural county is dependent on being a red county. (Relationship) -- Step 2. Set and justify alpha level. `\((\alpha = .001)\)` -- Step 3. Determine which sampling distribution `\((\chi^2)\)` -- Step 4. Calculate parameters of your sampling distribution under the null. * If `\(\chi^2\)`, calculate df. -- Step 5. Calculate test statistic under the null. --- `$$\chi^2_{df = (r-1)(c-1)} = \sum^r_{i=1}\sum^c_{j=1}\frac{(O_{ij}-E_{ij})^2}{E_{ij}}$$` We'll need to calculate the expected frequencies of each of the four cells. Expected frequencies should communicate what we expect _if the null hypothesis is true_, in this case, if the probability of being a red county is in fact independent of being a rural county. Recall from the [lecture on probability](https://uopsych.github.io/psy611/lectures/06-probability.html#15): If A and B are independent: `$$\Large \text{A and B }= P (A \cap B) = P(A)P(B)$$` We apply this rule to our contingency table. --- First, transform our row and column totals into proportions: | | Urban | Rural | Row Total | |--------------|:----------------:|:---------------:|:----------------:| | Red | 731 | 492 | 1223/3141 = .389 | | Blue | 1708 | 210 | 1918/3141 = .611 | | Column total | 2439/3141 = .777 | 702/3141 = .223 | 3141 | --- Second, use the probability of the union of independent events formula to calculate the joint probability of each cell: | | Urban | Rural | Row Total | |--------------|:-------------------:|:-------------------:|:---------:| | Red | (.389)(.777) = .302 | (.389)(.223) = .087 | .389 | | Blue | (.611)(.777) = .475 | (.611)(.223) = .136 | .611 | | Column total | .777 | .223 | 3141 | --- Lastly, multiply these proportions by the total number of counties to get the expected frequencies. | | Urban | Rural | Row Total | |--------------|:----------------------:|:---------------------:|:---------:| | Red | (.302)(3141) = 948.58 | (.087)(3141) = 273.27 | .389 | | Blue | (.475)(3141) = 1491.98 | (.136)(3141) = 427.18 | .611 | | Column total | .777 | .223 | 3141 | --- Now we calculate our test statistic: `$$\chi^2_{df = (r-1)(c-1)} = \sum^r_{i=1}\sum^c_{j=1}\frac{(O_{ij}-E_{ij})^2}{E_{ij}}$$` `$$\chi^2_{df = 1} = \frac{(731-948.58)^2}{948.58} + \frac{(492-273.27)^2}{273.27} +\\ \frac{(1708-1491.98)^2}{1491.98} + \frac{(210-427.18)^2}{427.18}\\ = 433.07$$` --- Step 6. Calculate probability of that test statistic or more extreme under the null, and compare to alpha. ```r pchisq(q = 433.07, df = 1, lower.tail = F) #remember that we're interested in this test statistic or greater ``` ``` ## [1] 3.489059e-96 ``` (No need to multiply by two here, because `\(\chi^2\)` tests are always one-tail tests.) Our _p_-value is smaller than alpha, so we reject the null hypothesis. --- Categorical data are discrete, and under the null hypothesis, we can think of the cell frequencies as arising from a binomial distribution with N trials and cell probabilities equal to the null hypothesis values `\((P_i)\)`. The observed frequencies are compared to the expected frequencies under the null hypothesis. The differences are capture in the form of the Pearson `\(\chi^2\)` statistic. The sampling distribution for that statistic is approximated by the `\(\chi^2\)` family of distributions. But, the `\(\chi^2\)` distribution is continuous and so can only approximate the sampling behavior of a discrete variable. That approximation will be poorest with small sample sizes, where the discrete nature of the data is more apparent. --- A number of solutions have been suggested to improve the accuracy of the `\(\chi^2\)` approximation with small samples. The most common is the Yates correction (also called the correction for continuity): `$$\chi^2_{df = k-1} = \sum^k_{i=1}\frac{(|O_i-E_i|-.5)^2}{E_i}$$` `$$\chi^2_{df = (r-1)(c-1)} = \sum^r_{i=1}\sum^c_{j=1}\frac{(|O_{ij}-E_{ij}| - .5)^2}{E_{ij}}$$` The correction penalizes the `\(\chi^2\)` statistic. The intent is to remove a positive bias for small samples and make it less likely that a false rejection will be made. The correction is recommended for small samples and when expected frequencies in any cell are low (some say 5, others say 10). --- Effect sizes frequently accompany chi-square tests of independence. The particular effect size used depends on whether the two-way contingency table is 2 x 2 or has more than 2 categories for one of the nominal variables. Effect sizes for 2 x 2 tables: * Phi coefficient * Odds ratio Effect sizes for larger two-way tables: * Cramer’s V --- The phi `\((\phi)\)` coefficient is simply the Pearson product-moment correlation applied to two binary variables. It has the usual range for correlations (-1 to 1) and when squared has the usual "proportion of variance shared" interpretation. It can be calculated in the usual way or it can be obtained from the `\(\chi^2\)` statistic for the independence test: `$$\phi = \sqrt{\frac{\chi^2}{N}}$$` --- ```r # as a correlation (require numeric variables) cor(as.numeric(suicide$depression), as.numeric(suicide$attempt)) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.156701 ``` ```r # from the test statistic chi_fit = chisq.test(table(suicide$depression, suicide$attempt), correct = F) sqrt(chi_fit$statistic/nrow(suicide)) ``` ``` ## X-squared ## 0.156701 ``` Proportion of variance shared: ```r cor(as.numeric(suicide$depression), as.numeric(suicide$attempt))^2 ``` ``` ## [1] 0.02455521 ``` --- The odds ratio effect size begins with frequencies. **Observed** <table style="border-collapse:collapse; border:none;"> <tr> <th style="border-top:double; text-align:center; font-style:italic; font-weight:normal; border-bottom:1px solid;" rowspan="2">Depression</th> <th style="border-top:double; text-align:center; font-style:italic; font-weight:normal;" colspan="2">Suicide</th> <th style="border-top:double; text-align:center; font-style:italic; font-weight:normal; font-weight:bolder; font-style:italic; border-bottom:1px solid; " rowspan="2">Total</th> </tr> <tr> <td style="border-bottom:1px solid; text-align:center; padding:0.2cm;">No Attempt</td> <td style="border-bottom:1px solid; text-align:center; padding:0.2cm;">Attempt</td> </tr> <tr> <td style="padding:0.2cm; text-align:left; vertical-align:middle;">Nondepressed</td> <td style="padding:0.2cm; text-align:center; "><span style="color:black;">70</span></td> <td style="padding:0.2cm; text-align:center; "><span style="color:black;">4</span></td> <td style="padding:0.2cm; text-align:center; "><span style="color:black;">74</span></td> </tr> <tr> <td style="padding:0.2cm; text-align:left; vertical-align:middle;">Depressed</td> <td style="padding:0.2cm; text-align:center; "><span style="color:black;">267</span></td> <td style="padding:0.2cm; text-align:center; "><span style="color:black;">72</span></td> <td style="padding:0.2cm; text-align:center; "><span style="color:black;">339</span></td> </tr> <tr> <td style="padding:0.2cm; border-bottom:double; font-weight:bolder; font-style:italic; text-align:left; vertical-align:middle;">Total</td> <td style="padding:0.2cm; text-align:center; border-bottom:double;"><span style="color:black;">337</span></td> <td style="padding:0.2cm; text-align:center; border-bottom:double;"><span style="color:black;">76</span></td> <td style="padding:0.2cm; text-align:center; border-bottom:double;"><span style="color:black;">413</span></td> </tr> </table> --- The odds ratio effect size begins with frequencies. **Observed** | | No Attempt | Attempt | Row Total | |--------------|:----------:|:-------:|:---------:| | Nondepressed | `\(O_{11}\)` | `\(O_{12}\)`| `\(O_{1.}\)` | | Depressed | `\(O_{21}\)` | `\(O_{22}\)`| `\(O_{2.}\)` | | Column total | `\(O_{.1}\)` | `\(O_{.2}\)`| `\(O_{..}\)` | .pull-left[ * SA = Suicide Attempt * NR = Nondepressed Relatives * DR = Depressed Relatives From the cell and marginal frequencies we can define the following: ] .pull-right[ `$$P(SA|NR) = \frac{O_{12}}{O_{1.}}$$` `$$P(SA|DR) = \frac{O_{22}}{O_{2.}}$$` ] --- The odds ratio effect size begins with frequencies. **Observed** | | No Attempt | Attempt | Row Total | |--------------|:----------:|:-------:|:---------:| | Nondepressed | `\(O_{11}\)` | `\(O_{12}\)`| `\(O_{1.}\)` | | Depressed | `\(O_{21}\)` | `\(O_{22}\)`| `\(O_{2.}\)` | | Column total | `\(O_{.1}\)` | `\(O_{.2}\)`| `\(O_{..}\)` | .pull-left[ * SA = Suicide Attempt * NR = Nondepressed Relatives * DR = Depressed Relatives From the cell and marginal frequencies we can define the following: ] .pull-right[ `$$Odds(SA|NR) = \frac{P(SA|NR)}{1-P(SA|NR)}$$` `$$Odds(SA|DR) = \frac{P(SA|DR)}{1-P(SA|DR)}$$` ] --- The odds ratio effect size begins with frequencies. **Observed** | | No Attempt | Attempt | Row Total | |--------------|:----------:|:-------:|:---------:| | Nondepressed | `\(O_{11}\)` | `\(O_{12}\)`| `\(O_{1.}\)` | | Depressed | `\(O_{21}\)` | `\(O_{22}\)`| `\(O_{2.}\)` | | Column total | `\(O_{.1}\)` | `\(O_{.2}\)`| `\(O_{..}\)` | .pull-left[ * SA = Suicide Attempt * NR = Nondepressed Relatives * DR = Depressed Relatives From the cell and marginal frequencies we can define the following: ] .pull-right[ `$$OddsRatio = \frac{Odds(SA|NR)}{Odds(SA|DR)}$$` ] --- `$$P(SA|NR) = \frac{4}{74} = .0541$$` `$$P(SA|DR) = \frac{72}{339} = .212$$` `$$Odds(SA|NR) = \frac{.0541}{1-.0541} = .0572$$` `$$Odds(SA|DR) = \frac{.212}{1-.212} = .269$$` `$$Odds Ratio = \frac{.269}{.0572} = 4.72$$` The odds of attempting suicide if you have depressed relatives are 4.72 times the odds of attempting suicide if you don’t have depressed relatives. --- There is a convenient short-cut calculation based on the cell frequencies: `$$Odds Ratio = \frac{O_{11}O_{22}}{O_{12}O_{21}} = \frac{70(72)}{4(267)} = 4.72$$` --- When tables are larger than 2 x 2, Cramer’s V is the most common effect size and follows in form the calculation of the phi coefficient: `$$V = \sqrt{\frac{\chi^2}{min(r-1,c-1)(N)}}$$` When df=1 (a 2 x 2 table), `\(V = \phi\)`. In all cases, it is bounded by 0 (no association) and 1 (perfect association). --- ## The usefulness of `\(\chi^2\)` How often will you conducted a `\(chi^2\)` goodness of fit test on raw data? -- * (Probably) never How often will you come across `\(\chi^2\)` tests? -- * (Probably) a lot! The goodness of fit test is used to statistically test the how well a model fits data. --- To calculate Goodness of Fit of a model to data, you build a statistical model of the process as you believe it is in the world. - example: literacy ~ age + parental involvement Then you estimate each subject's predicted value based on your model. You compare each subject's predicted value to their actual value -- the difference is called the **residual** ( `\(\varepsilon\)` ). If your model is a good fit, then `$$\Sigma_1^N\varepsilon^2 = \chi^2$$` which we compare to the distribution of `\(\chi^2_{N-p}\)` . Significant chi-square tests suggest the model does not fit -- the data have values that are far away from "expected." --- When we move from categorical outcomes to variables measured on an interval or ratio scale, we become interested in means rather than frequencies. Comparing means is usually done with the *t*-test, of which there are several forms. The one-sample *t*-test is appropriate when a single sample mean is compared to a population mean but the population standard deviation is unknown. A sample estimate of the population standard deviation is used instead. The appropriate sampling distribution is the t-distribution, with N-1 degrees of freedom. `$$t_{df=N-1} = \frac{\bar{X}-\mu}{\frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}}}$$` The heavier tails of the t-distribution, especially for small N, are the penalty we pay for having to estimate the population standard deviation from the sample. --- ### One-sample *t*-tests *t*-tests were developed by William Sealy Gosset, who was a chemist studying the grains used in making beer. (He worked for Guinness.) * Specifically, he wanted to know whether particular strains of grain made better or worse beer than the standard. * He developed the *t*-test, to test small samples of beer against a population with an unknown standard deviation. * Probably had input from Karl Pearson and Ronald Fisher * Published this as "Student" because Guinness wouldn't let him share company secrets. --- ### One-sample *t*-tests We've already been covering one-sample *t*-tests, but let's formally walk through some of the steps and how this differs from a z-test. | | Z-test | *t*-test | | --|--------|--------| | `\(\large{\mu}\)` | known | known | | `\(\sigma\)` | known |unknown | | sem or `\(\sigma_M\)` | `\(\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{N}}\)` | `\(\frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}}\)` | |Probability distribution | standard normal | t | | DF | none | N-1 | | Tails | One or two | One or two | | Critical value ( `\(\alpha = .05, two-tailed\)` | 1.96 | Depends on DF | --- ### When you assume... ...you can run a parametric statistical test! **Assumptions of the one-sample *t*-test** **Normality.** We assume the sampling distribution of the mean is normally distributed. Under what two conditions can we be assured that this is true? **Independence.** Observations in the dataset are not associated with one another. Put another way, collecting a score from Participant A doesn't tell me anything about what Participant B will say. How can we be safe in this assumption? --- ### A brief example Using the same Census at School data, we find that Oregon students who participated in a memory game ( `\(N = 227\)` ) completed the game in an average time of 49.1 seconds ( `\(s = 13.4\)` ). We know that the average US student completed the game in 45.04 seconds. How do our students compare? -- **Hypotheses** `\(H_0: \mu = 45.05\)` `\(H_1: \mu \neq 45.05\)` --- `$$\mu = 45.05$$` `$$N = 227$$` $$ \bar{X} = 49.1 $$ $$ s = 13.4 $$ ```r t.test(x = school$Score_in_memory_game, mu = 45.05, alternative = "two.sided") ``` ``` ## ## One Sample t-test ## ## data: school$Score_in_memory_game ## t = 4.2652, df = 196, p-value = 3.104e-05 ## alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 45.05 ## 95 percent confidence interval: ## 47.24269 51.01427 ## sample estimates: ## mean of x ## 49.12848 ``` --- ```r lsr::oneSampleTTest(x = school$Score_in_memory_game, mu = 45.05, one.sided = FALSE) ``` ``` ## ## One sample t-test ## ## Data variable: school$Score_in_memory_game ## ## Descriptive statistics: ## Score_in_memory_game ## mean 49.128 ## std dev. 13.421 ## ## Hypotheses: ## null: population mean equals 45.05 ## alternative: population mean not equal to 45.05 ## ## Test results: ## t-statistic: 4.265 ## degrees of freedom: 196 ## p-value: <.001 ## ## Other information: ## two-sided 95% confidence interval: [47.243, 51.014] ## estimated effect size (Cohen's d): 0.304 ``` --- ## Shifting confidence intervals <!-- --> --- # Cohen's D Cohen suggested one of the most common effect size estimates—the standardized mean difference—useful when comparing a group mean to a population mean or two group means to each other. `$$\delta = \frac{\mu_1 - \mu_0}{\sigma} \approx d = \frac{\bar{X}-\mu}{\hat{\sigma}}$$` -- Cohen’s d is in the standard deviation (Z) metric. --- Cohens’s d for these data is .30. In other words, the sample mean differs from the population mean by .30 standard deviation units. Cohen (1988) suggests the following guidelines for interpreting the size of d: .large[ - .2 = Small - .5 = Medium - .8 = Large ] .small[Cohen, J. (1988), Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd Ed.). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.] --- Another useful metric is the overlap between the two distributions -- the smaller the overlap, the farther apart the distributions <!-- --> --- ### The usefulness of the one-sample *t*-test How often will you conducted a one-sample *t*-test on raw data? -- * (Probably) never How often will you come across one-sample *t*-tests? -- * (Probably) a lot! The one-sample *t*-test is used to test coefficients in a model. --- ```r model = lm(health ~ education, data = spi) summary(model) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = health ~ education, data = spi) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -2.6683 -0.5896 0.3317 0.5284 1.6071 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 3.353512 0.036015 93.116 < 2e-16 *** ## education 0.039348 0.007732 5.089 3.8e-07 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 0.9733 on 3251 degrees of freedom ## (747 observations deleted due to missingness) ## Multiple R-squared: 0.007903, Adjusted R-squared: 0.007598 ## F-statistic: 25.9 on 1 and 3251 DF, p-value: 3.803e-07 ``` --- # Next time... Comparing two means