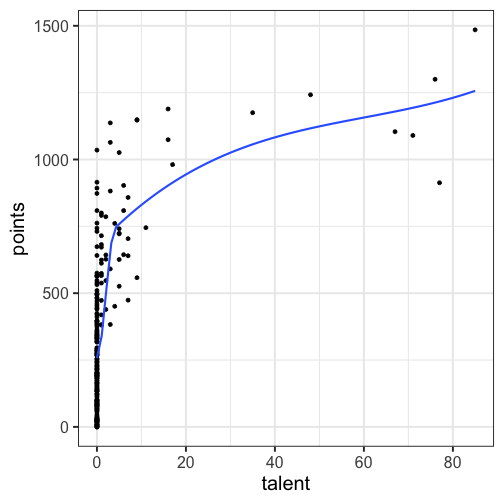

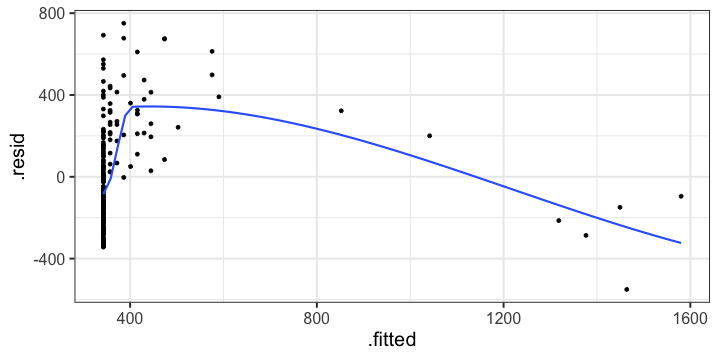

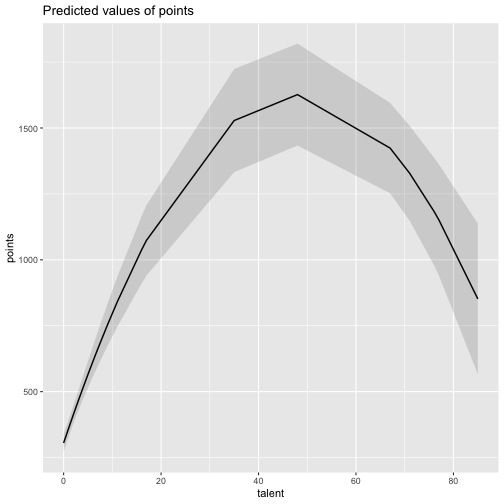

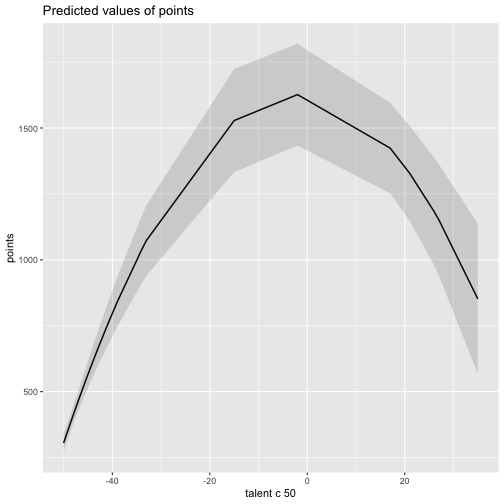

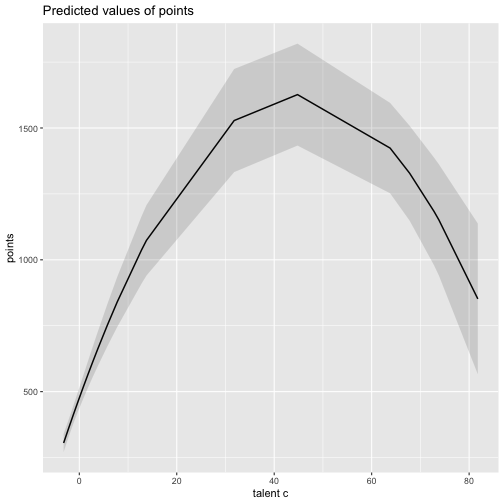

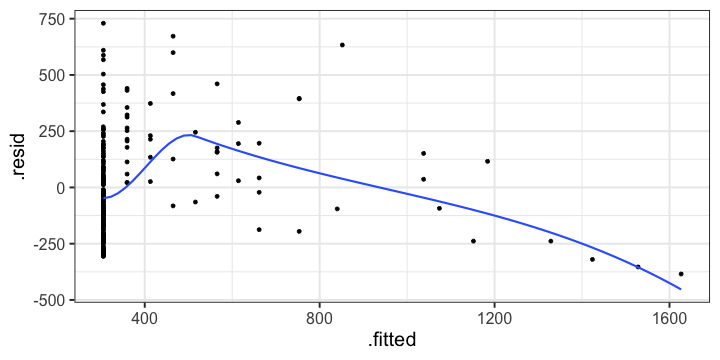

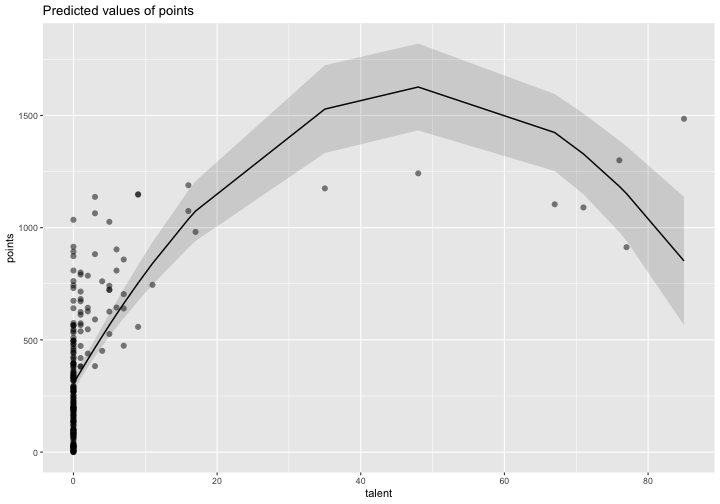

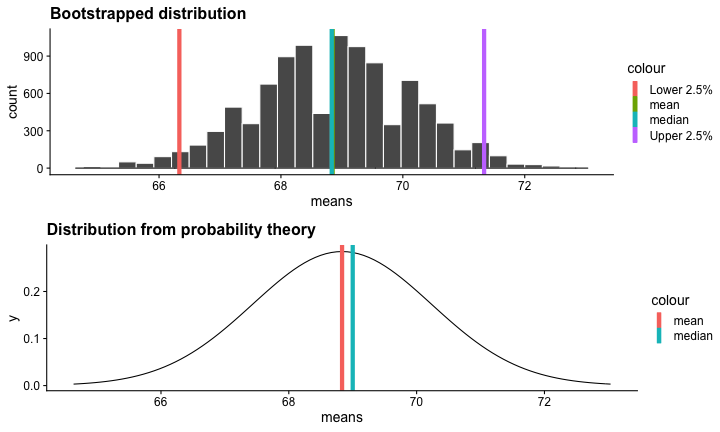

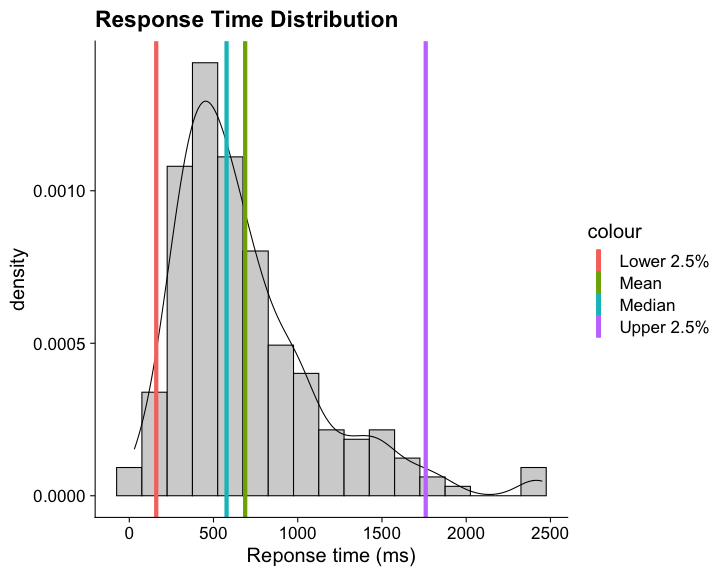

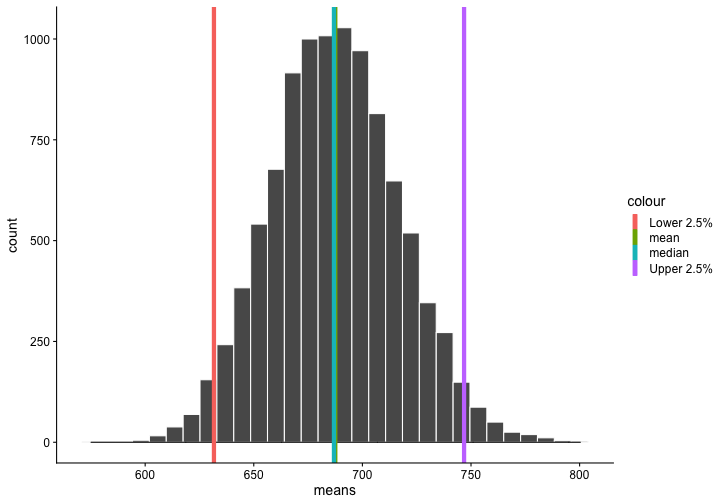

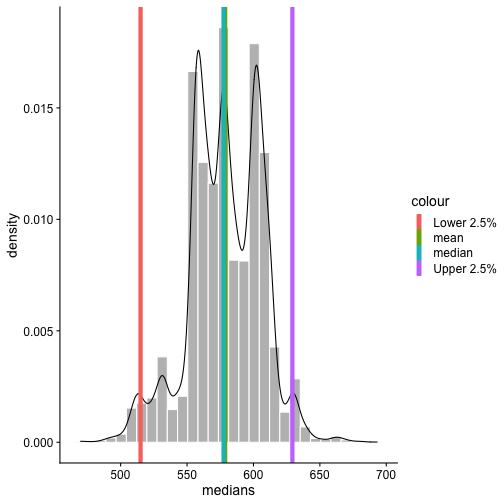

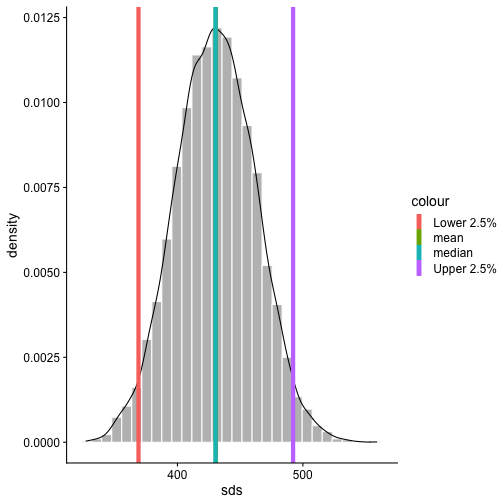

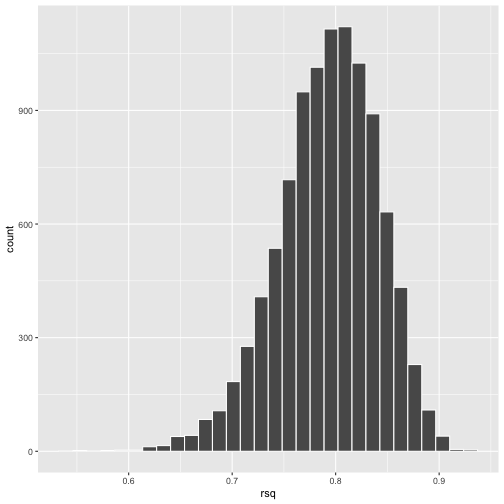

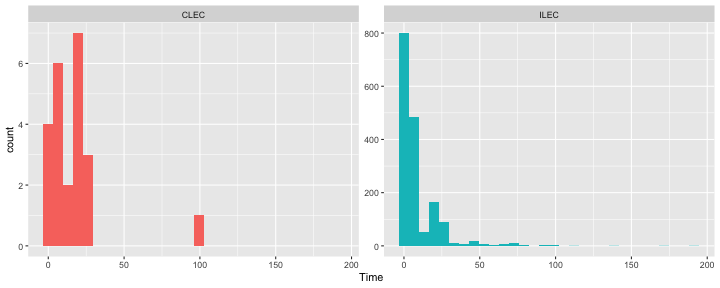

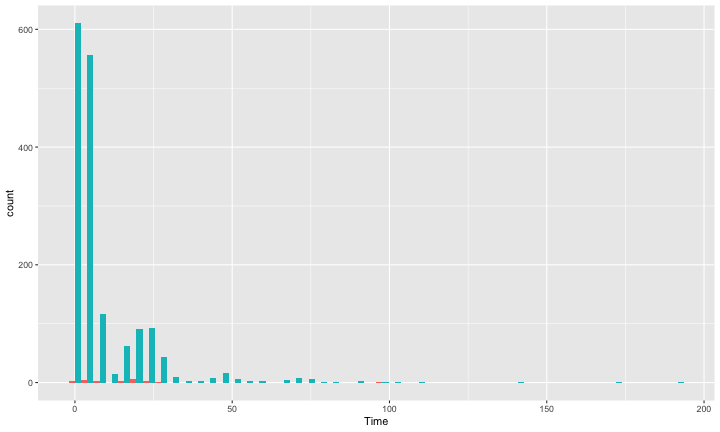

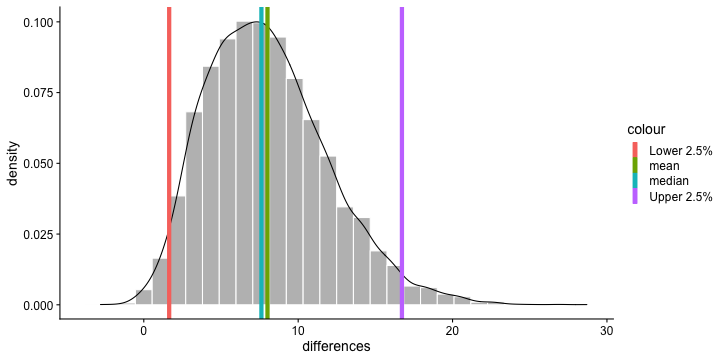

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Polynomials and Bootstrapping --- class: inverse ## Non-linear relationships Linear lines often make bad predictions -- very few processes that we study actually have linear relationships. For example, effort had diminishing returns (e.g., log functions), or small advantages early in life can have significant effects on mid-life outcones (e.g., exponentional functions). In cases where the direction of the effect is constant but changing in magnitude, the best way to handle the data is to transform a variable (usually the outcome) and run linear analyses. ```r log_y = ln(y) lm(log_y ~ x) ``` --- ## Polynomial relationships Other processes represent changes in the directon of relationship -- for example, it is believed that a small amount of anxiety is benefitial for performance on some tasks (positive direction) but too much is detrimental (negative direction). When the shape of the effect includes change(s) in direction, then a polynomial term(s) may be more appropriate. It should be noted that polynomials are often a poor approximation for a non-linear effect of X on Y. However, correctly testing for non-linear effects usually requires (a) a lot of data and (b) making a number of assumptions about the data. Polynomial regression can be a useful tool for exploratory analysis and in cases when data are limited in terms of quantity and/or quality. --- ## Polynomial regression Polynomial regression is most often a form of hierarchical regressoin that systematically tests a series of higher order functions for a single variable. $$ `\begin{aligned} \large \textbf{Linear: } \hat{Y} &= b_0 + b_1X \\ \large \textbf{Quadtratic: } \hat{Y} &= b_0 + b_1X + b_2X^2 \\ \large \textbf{Cubic: } \hat{Y} &= b_0 + b_1X + b_2X^2 + b_3X^3\\ \end{aligned}` $$ ---  --- ### Example Can a team have too much talent? Researchers hypothesized that teams with too many talented players have poor intrateam coordination and therefore perform worse than teams with a moderate amount of talent. To test this hypothesis, they looked at 208 international football teams. Talent was the percentage of players during the 2010 and 2014 World Cup Qualifications phases who also had contracts with elite club teams. Performance was the number of points the team earned during these same qualification phases. ```r football = read.csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/uopsych/psy612/master/data/swaab.csv") ``` .small[Swaab, R.I., Schaerer, M, Anicich, E.M., Ronay, R., and Galinsky, A.D. (2014). [The too-much-talent effect: Team interdependence determines when more talent is too much or not enough.](https://www8.gsb.columbia.edu/cbs-directory/sites/cbs-directory/files/publications/Too%20much%20talent%20PS.pdf) _Psychological Science 25_(8), 1581-1591.] --- .pull-left[ ```r head(football) ``` ``` ## country points talent ## 1 Spain 1485 85 ## 2 Germany 1300 76 ## 3 Brazil 1242 48 ## 4 Portugal 1189 16 ## 5 Argentina 1175 35 ## 6 Switzerland 1149 9 ``` ] .pull-right[ ```r ggplot(football, aes(x = talent, y = points)) + geom_point() + geom_smooth(se = F) + theme_bw(base_size = 20) ``` <!-- --> ] --- ```r mod1 = lm(points ~ talent, data = football) library(broom) aug1 = augment(mod1) ggplot(aug1, aes(x = .fitted, y = .resid)) + geom_point() + geom_smooth(se = F) + theme_bw(base_size = 20) ``` <!-- --> --- ```r mod2 = lm(points ~ talent + I(talent^2), data = football) summary(mod2) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = points ~ talent + I(talent^2), data = football) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -384.66 -193.82 -35.34 152.11 729.66 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 305.34402 17.62668 17.323 < 0.0000000000000002 *** ## talent 54.89787 5.46864 10.039 < 0.0000000000000002 *** ## I(talent^2) -0.57022 0.07499 -7.604 0.00000000000101 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 236.3 on 205 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.4644, Adjusted R-squared: 0.4592 ## F-statistic: 88.87 on 2 and 205 DF, p-value: < 0.00000000000000022 ``` --- ```r library(sjPlot) plot_model(mod2, type = "pred", terms = c("talent")) ``` <!-- --> --- ## Interpretation The intercept is the predicted value of Y when x = 0 -- this is always the interpretation of the intercept, no matter what kind of regression model you're running. The `\(b_1\)` coefficient is the tangent to the curve when X=0. In other words, this is the rate of change when X is equal to 0. If 0 is not a meaningful value on your X, you may want to center, as this will tell you the rate of change at the mean of X. ```r football$talent_c50 = football$talent - 50 mod2_50 = lm(points ~ talent_c50 + I(talent_c50^2), data = football) ``` --- ```r summary(mod2_50) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = points ~ talent_c50 + I(talent_c50^2), data = football) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -384.66 -193.82 -35.34 152.11 729.66 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 1624.68872 97.18998 16.717 < 0.0000000000000002 *** ## talent_c50 -2.12408 2.56568 -0.828 0.409 ## I(talent_c50^2) -0.57022 0.07499 -7.604 0.00000000000101 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 236.3 on 205 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.4644, Adjusted R-squared: 0.4592 ## F-statistic: 88.87 on 2 and 205 DF, p-value: < 0.00000000000000022 ``` --- <!-- --> --- Or you can choose another value to center your predictor on, if there's a value that has a particular meaning or interpretation. ```r football$talent_c = football$talent - mean(football$talent) mod2_c = lm(points ~ talent_c + I(talent_c^2), data = football) ``` --- ```r mean(football$talent) ``` ``` ## [1] 3.216346 ``` ```r summary(mod2_c) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = points ~ talent_c + I(talent_c^2), data = football) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -384.66 -193.82 -35.34 152.11 729.66 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 476.01572 19.94656 23.865 < 0.0000000000000002 *** ## talent_c 51.22982 5.00212 10.242 < 0.0000000000000002 *** ## I(talent_c^2) -0.57022 0.07499 -7.604 0.00000000000101 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 236.3 on 205 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.4644, Adjusted R-squared: 0.4592 ## F-statistic: 88.87 on 2 and 205 DF, p-value: < 0.00000000000000022 ``` --- <!-- --> --- ## Interpretation The `\(b_2\)` coefficient indexes the acceleration, which is how much the slope is going to change. More specifically, `\(2 \times b_2\)` is the acceleration: the rate of change in `\(b_1\)` for a 1-unit change in X. You can use this to calculate the slope of the tangent line at any value of X you're interested in: `$$\large b_1 + (2\times b_2\times X)$$` --- ```r tidy(mod2) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 3 x 5 ## term estimate std.error statistic p.value ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 (Intercept) 305. 17.6 17.3 5.22e-42 ## 2 talent 54.9 5.47 10.0 1.53e-19 ## 3 I(talent^2) -0.570 0.0750 -7.60 1.01e-12 ``` .pull-left[ **At X = 10** ```r 54.9 + (2*-.570*10) ``` ``` ## [1] 43.5 ``` ] .pull-right[ **At X = 70** ```r 54.9 + (2*-.570*70) ``` ``` ## [1] -24.9 ``` ] --- ## Polynomials are interactions An term for `\(X^2\)` is a term for `\(X \times X\)` or the multiplication of two independent variables holding the same values. ```r football$talent_2 = football$talent*football$talent tidy(lm(points ~ talent + talent_2, data = football)) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 3 x 5 ## term estimate std.error statistic p.value ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 (Intercept) 305. 17.6 17.3 5.22e-42 ## 2 talent 54.9 5.47 10.0 1.53e-19 ## 3 talent_2 -0.570 0.0750 -7.60 1.01e-12 ``` --- ## Polynomials are interactions Put another way: `$$\large \hat{Y} = b_0 + b_1X + b_2X^2$$` `$$\large \hat{Y} = b_0 + \frac{b_1}{2}X + \frac{b_1}{2}X + b_2(X \times X)$$` The interaction term in another model would be interpreted as "how does the slope of X change as I move up in Z?" -- here, we ask "how does the slope of X change as we move up in X?" --- ## When should you use polynomial terms? You may choose to fit a polynomial term after looking at a scatterplot of the data or looking at residual plots. A U-shaped curve may be indicative that you need to fit a quadratic form -- although, as we discussed before, you may actually be measuring a different kind of non-linear relationship. Polynomial terms should mostly be dictated by theory -- if you don't have a good reason for thinking there will be a change in sign, then a polynomial is not right for you. And, of course, if you fit a polynomial regression, be sure to once again check your diagnostics before interpreting the coefficients. --- ```r aug2 = augment(mod2) ggplot(aug2, aes(x = .fitted, y = .resid)) + geom_point() + geom_smooth(se = F) + theme_bw(base_size = 20) ``` <!-- --> --- ```r plot_model(mod2, type = "pred", show.data = T) ``` ``` ## $talent ``` <!-- --> --- ## Bootstrapping In bootstrapping, the theoretical sampling distribution is assumed to be unknown or unverifiable. Under the weak assumption that the sample in hand is representative of some population, then that population sampling distribution can be built empirically by randomly sampling with replacement from the sample. The resulting empirical sampling distribution can be used to construct confidence intervals and make inferences. --- ### Illustration Imagine you had a sample of 6 people: Rachel, Monica, Phoebe, Joey, Chandler, and Ross. To bootstrap their heights, you would draw from this group many samples of 6 people *with replacement*, each time calculating the average height of the sample. ``` ## [1] "Joey" "Phoebe" "Chandler" "Chandler" "Ross" "Phoebe" ``` ``` ## [1] 70.5 ``` ``` ## [1] "Rachel" "Chandler" "Joey" "Rachel" "Rachel" "Joey" ``` ``` ## [1] 67.83333 ``` ``` ## [1] "Rachel" "Chandler" "Rachel" "Rachel" "Monica" "Ross" ``` ``` ## [1] 67.5 ``` ``` ## [1] "Rachel" "Monica" "Rachel" "Joey" "Phoebe" "Ross" ``` ``` ## [1] 67.66667 ``` ``` ## [1] "Joey" "Rachel" "Monica" "Ross" "Chandler" "Rachel" ``` ``` ## [1] 68.33333 ``` ``` ## [1] "Joey" "Chandler" "Monica" "Chandler" "Ross" "Ross" ``` ``` ## [1] 70.83333 ``` ``` ## [1] "Ross" "Rachel" "Rachel" "Chandler" "Monica" "Rachel" ``` ``` ## [1] 67.5 ``` ``` ## [1] "Monica" "Chandler" "Ross" "Rachel" "Ross" "Monica" ``` ``` ## [1] 68.83333 ``` ??? ```r heights ``` ``` ## Rachel Monica Phoebe Joey Chandler Ross ## 65 65 68 70 72 73 ``` --- ### Illustration ```r boot = 10000 friends = c("Rachel", "Monica", "Phoebe", "Joey", "Chandler", "Ross") heights = c(65, 65, 68, 70, 72, 73) sample_means = numeric(length = boot) for(i in 1:boot){ this_sample = sample(heights, size = length(heights), replace = T) sample_means[i] = mean(this_sample) } ``` --- ## Illustration <!-- --> --- ### Example A sample of 216 response times. What is their central tendency and variability? There are several candidates for central tendency (e.g., mean, median) and for variability (e.g., standard deviation, interquartile range). Some of these do not have well understood theoretical sampling distributions. For the mean and standard deviation, we have theoretical sampling distributions to help us, provided we think the mean and standard deviation are the best indices. For the others, we can use bootstrapping. --- <!-- --> --- ### Bootstrapping Before now, if we wanted to estimate the mean and the 95% confidence interval around the mean, we would find the theoretical sampling distribution by scaling a t-distribution to be centered on the mean of our sample and have a standard deviation equal to `\(\frac{s}{\sqrt{N}}.\)` But we have to make many assumptions to use this sampling distribution, and we may have good reason not to. Instead, we can build a population sampling distribution empirically by randomly sampling with replacement from the sample. --- ## Response time example ```r boot = 10000 response_means = numeric(length = boot) for(i in 1:boot){ sample_response = sample(response, size = 216, replace = T) response_means[i] = mean(sample_response) } ``` <!-- --> --- ```r mean(response_means) ``` ``` ## [1] 687.5221 ``` ```r median(response_means) ``` ``` ## [1] 686.9085 ``` ```r quantile(response_means, probs = c(.025, .975)) ``` ``` ## 2.5% 97.5% ## 631.6661 746.8103 ``` What about something like the median? --- ### bootstrapped distribution of the median ```r boot = 10000 response_med = numeric(length = boot) for(i in 1:boot){ sample_response = sample(response, size = 216, replace = T) response_med[i] = median(sample_response) } ``` .pull-left[ <!-- --> ] .pull-right[ ```r mean(response_med) ``` ``` ## [1] 578.6673 ``` ```r median(response_med) ``` ``` ## [1] 577.5063 ``` ```r quantile(response_med, probs = c(.025, .975)) ``` ``` ## 2.5% 97.5% ## 514.9828 629.3005 ``` ] --- ### bootstrapped distribution of the standard deviation ```r boot = 10000 response_sd = numeric(length = boot) for(i in 1:boot){ sample_response = sample(response, size = 216, replace = T) response_sd[i] = sd(sample_response) } ``` .pull-left[ <!-- --> ] .pull-right[ ```r mean(response_sd) ``` ``` ## [1] 430.5541 ``` ```r median(response_sd) ``` ``` ## [1] 430.3614 ``` ```r quantile(response_sd, probs = c(.025, .975)) ``` ``` ## 2.5% 97.5% ## 368.9656 492.1912 ``` ] --- You can bootstrap estimates and 95% confidence intervals for *any* statistics you'll need to estimate. The `boot` function provides some functions to speed this process along. ```r library(boot) # function to obtain R-Squared from the data rsq <- function(data, indices) { d <- data[indices,] # allows boot to select sample fit <- lm(mpg~wt+disp, data=d) # this is the code you would have run return(summary(fit)$r.square) } # bootstrapping with 10000 replications results <- boot(data=mtcars, statistic=rsq, R=10000) ``` --- .pull-left[ ```r data.frame(rsq = results$t) %>% ggplot(aes(x = rsq)) + geom_histogram(color = "white", bins = 30) ``` <!-- --> ] .pull-right[ ```r median(results$t) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.7962501 ``` ```r boot.ci(results, type = "perc") ``` ``` ## BOOTSTRAP CONFIDENCE INTERVAL CALCULATIONS ## Based on 10000 bootstrap replicates ## ## CALL : ## boot.ci(boot.out = results, type = "perc") ## ## Intervals : ## Level Percentile ## 95% ( 0.6871, 0.8773 ) ## Calculations and Intervals on Original Scale ``` ] --- ### Example 2 Samples of service waiting times for Verizon’s (ILEC) versus other carriers (CLEC) customers. In this district, Verizon must provide line service to all customers or else face a fine. The question is whether the non-Verizon customers are getting ignored or facing greater variability in waiting times. ```r Verizon = read.csv(here("data/Verizon.csv")) ``` <!-- --> --- <!-- --> ``` ## ## CLEC ILEC ## 23 1664 ``` --- There's no world in which these data meet the typical assumptions of an independent samples t-test. To estimate mean differences we can use boostrapping. Here, we'll resample with replacement separately from the two samples. ```r boot = 10000 difference = numeric(length = boot) subsample_CLEC = Verizon %>% filter(Group == "CLEC") subsample_ILEC = Verizon %>% filter(Group == "ILEC") for(i in 1:boot){ sample_CLEC = sample(subsample_CLEC$Time, size = nrow(subsample_CLEC), replace = T) sample_ILEC = sample(subsample_ILEC$Time, size = nrow(subsample_ILEC), replace = T) difference[i] = mean(sample_CLEC) - mean(sample_ILEC) } ``` --- <!-- --> The difference in means is 7.62 `\([1.64,16.72]\)`. --- ### Bootstrapping Summary Bootstrapping can be a useful tool to estimate parameters when 1. you've violated assumptions of the test (i.e., normality, homoskedasticity) 2. you have good reason to believe the sampling distribution is not normal, but don't know what it is 3. there are other oddities in your data, like very unbalanced samples This allows you to create a confidence interval around any statistic you want -- Cronbach's alpha, ICC, Mahalanobis Distance, `\(R^2\)`, AUC, etc. * You can test whether these statistics are significantly different from any other value -- how? --- ### Bootstrapping Summary Bootstrapping will NOT help you deal with: * dependence between observations -- for this, you'll need to explicity model dependence (e.g., multilevel model, repeated measures ANOVA) * improperly specified models or forms -- use theory to guide you here * measurement error -- why bother? --- class: inverse ## Next time...