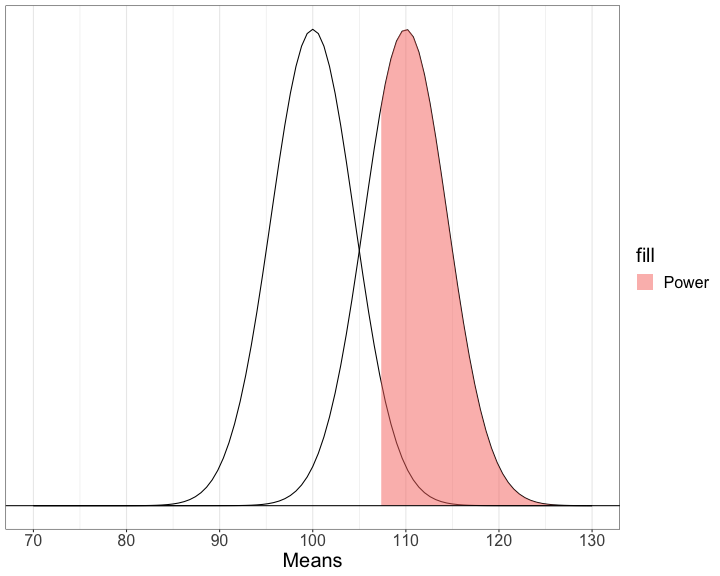

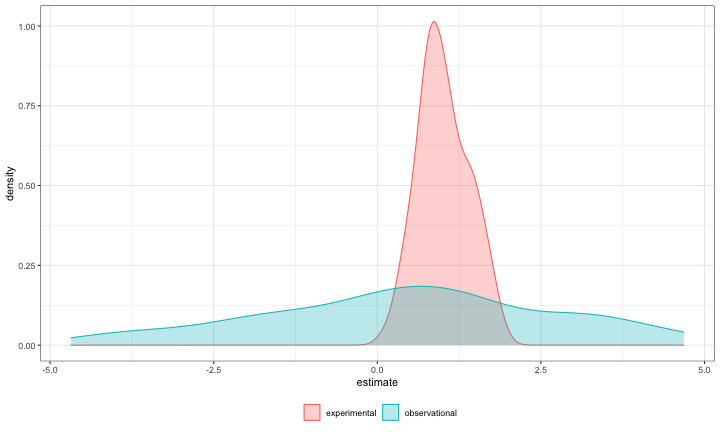

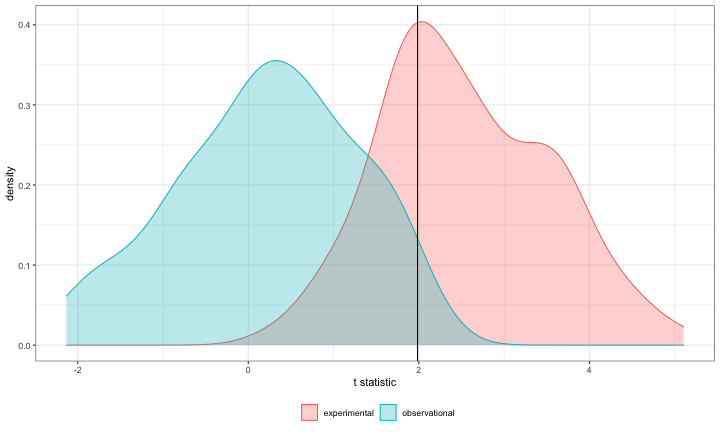

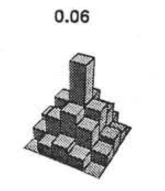

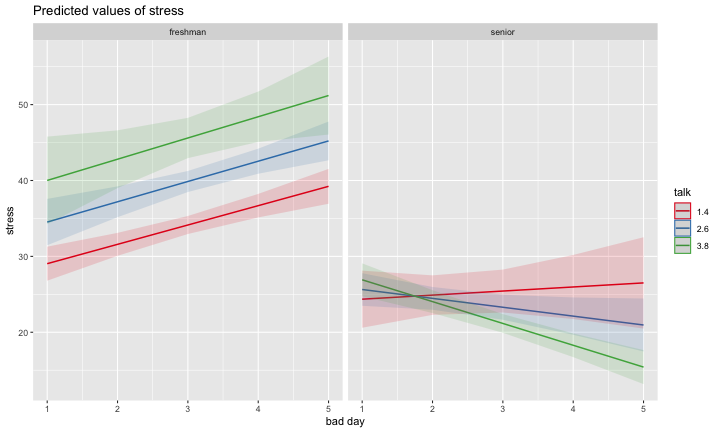

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Interactions (Power analyses and 3-way interactions) --- ## Announcements * Download and install LaTex before lab tomorrow. * Homework 3 due next Friday --- ## Power The likelihood of finding an effect *if the effect actually exists.* Power gets larger as we: * increase our sample size * reduce (error) variance * raise our Type I error rate * study larger effects --- <!-- --> --- ## Power in multiple regression (additive effects) When calculating power for the omnibus test, use the expected multiple `\(R^2\)` value to calculate an effect size: `$$\large f^2 = \frac{R^2}{1-R^2}$$` --- ### Omnibus power ```r R2 = .10 (f = R2/(1-R2)) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.1111111 ``` ```r library(pwr) pwr.f2.test(u = 3, # number of predictors in the model f2 = f, sig.level = .05, #alpha power =.90) # desired power ``` ``` ## ## Multiple regression power calculation ## ## u = 3 ## v = 127.5235 ## f2 = 0.1111111 ## sig.level = 0.05 ## power = 0.9 ``` `v` is the denominator df of freedom, so the number of participants needed is v + p + 1. --- ### Coefficient power To estimate power for a single coefficient, you need to consider (1) how much variance is accounted for by just the variable and (2) how much variance you'll account for in Y overall. `$$\large f^2 = \frac{R^2_Y-R^2_{Y.X}}{1-R_Y^2}$$` --- ### Coefficient power ```r R2 = .10 RX1 = .03 (f = (R2-RX1)/(1-R2)) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.07777778 ``` ```r pwr.f2.test(u = 3, # number of predictors in the model f2 = f, sig.level = .05, #alpha power =.90) # desired power ``` ``` ## ## Multiple regression power calculation ## ## u = 3 ## v = 182.1634 ## f2 = 0.07777778 ## sig.level = 0.05 ## power = 0.9 ``` `v` is the denominator df of freedom, so the number of participants needed is v + p + 1. --- ## Effect sizes (interactions) To start our discussion on powering interaction terms, we need to first consider the effect size of an interaction. How big can we reasonably expect an interaction to be? - Interactions are always partialled effects - that is, we examine the relationship between the product of variables X and Z only after we have controlled for X and controlled for Z. - Think of XZ as a new variable (W). In any other regression model, what would we be concerned about in terms of our predictors? ??? The effect of XZ and Y will be made smaller as X or Z (or both) is related to the product -- the semi-partial correlation is always smaller than or equal to the zero-order correlation. --- ## McClelland and Judd (1993) Is it more difficult to find interaction effects in experimental studies or observational studies? -- What factors make it relatively easier to find interactions in experimental work? --- ### Factors influencing power in experimental studies - No measurement error of IV * don't have to guess what condition a participant is in * measurement error is exacerbated when two variables measured with error are multiplied by each other - Studies with experimental designs are more likely to yield cross-over interactions; observational studies may be restricted to fan interactions * cross-over interactions are easier to detect than fan interactions --- ### Factors influencing power in experimental studies - Researchers can concentrate scores on extreme ends on both X and Z. * increases variability in both X and Z, and in XZ * in observational studies, data tends to cluster around the mean - Researchers can also force orthogonality in X and Z. - Researchers can study the full range of X in an experiment. --- ### McClelland and Judd's simulation "For the experiment simulations, we used 2 X 2 factorial designs, with values of X and Z equal to +1 and —1 and an equal number of observations at each of the four combinations of X and Z values." ```r X = rep(c(-1,1), each = 50) Z = rep(c(-1,1), times = 50) table(X,Z) ``` ``` ## Z ## X -1 1 ## -1 25 25 ## 1 25 25 ``` --- ### McClelland and Judd's simulation "For the field study simulations, we used values of X and Z that varied between the extreme values of +1 and —1. ...values of X and Z were each sampled independently from a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.5. Values of X and Z were rounded to create equally spaced 9-point scales ranging from -1 to +1." ```r sim_con = function(n){ x = rnorm(n, mean = 0, sd = .5) # simulate from distribution outside_range = which(x > 1 | x < -1) # identify values outside range # if at least one outside range, do this while(length(outside_range) > 0){ # simulate just for values outside range x[outside_range] = rnorm(length(outside_range), 0, .5) outside_range = which(x > 1 | x < -1) # check } # convert to 9 point scale rounded = plyr::round_any(x, accuracy = .25) return(rounded) # output of function } ``` --- ### McClelland and Judd's simulation "For the field study simulations, we used values of X and Z that varied between the extreme values of +1 and —1. ...values of X and Z were each sampled independently from a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 0.5. Values of X and Z were rounded to create equally spaced 9-point scales ranging from -1 to +1." ```r set.seed(03032022) X = sim_con(100) Z = sim_con(100) table(X) ``` ``` ## X ## -1 -0.75 -0.5 -0.25 0 0.25 0.5 0.75 1 ## 2 7 10 22 16 17 18 5 3 ``` ```r cor(X,Z) ``` ``` ## [1] -0.1427566 ``` --- For the simulations of both the field studies and the experiments, `\(\beta_0 = 0, \beta_X=\beta_Z=\beta_{XZ} = 1.\)` There were 100 observations, and errors for the model were sampled from the same normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 4. ```r Y = 0 + 1*X + 1*Z + 1*X*Z + rnorm(n = 100, mean = 0, sd = 4) summary(lm(Y ~ X*Z)) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = Y ~ X * Z) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -11.5852 -2.3361 0.0421 2.4987 12.6863 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 0.8532 0.4322 1.974 0.0512 . ## X -0.8926 0.9387 -0.951 0.3441 ## Z -0.1403 1.0104 -0.139 0.8899 ## X:Z 3.2863 2.2175 1.482 0.1416 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 4.271 on 96 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.03114, Adjusted R-squared: 0.0008583 ## F-statistic: 1.028 on 3 and 96 DF, p-value: 0.3836 ``` --- From 100 simulations each, estimates of the model parameter `\(\beta_{XZ}\)` the moderator or interaction effect equaled 0.977 and 0.979 for the field studies and experiments, respectively. ```r set.seed(0303) sim = 100 N = 100 ``` .pull-left[ ```r # for experimental studies ebeta_xz = numeric(length = N) et_xz = numeric(length = N) for(i in 1:sim){ # simulate data X = rep(c(-1,1), each = N/2) Z = rep(c(-1,1), times = N/2) Y = 0 + 1*X + 1*Z + 1*X*Z + rnorm(n = N, mean = 0, sd = 4) #run model model = lm(Y ~ X*Z) coef = coef(summary(model)) #extract coefficients beta = coef["X:Z", "Estimate"] t_val = coef["X:Z", "t value"] #save to vectors ebeta_xz[i] = beta et_xz[i] = t_val } ``` ] .pull-right[ ```r # for observational studies obeta_xz = numeric(length = N) ot_xz = numeric(length = N) for(i in 1:sim){ # simulate data X = sim_con(N) Z = sim_con(N) Y = 0 + 1*X + 1*Z + 1*X*Z + rnorm(n = N, mean = 0, sd = 4) #run model model = lm(Y ~ X*Z) coef = coef(summary(model)) #extract coefficients beta = coef["X:Z", "Estimate"] t_val = coef["X:Z", "t value"] #save to vectors obeta_xz[i] = beta ot_xz[i] = t_val } ``` ] --- ```r mean(ebeta_xz) ``` ``` ## [1] 1.015903 ``` ```r mean(obeta_xz) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.4579002 ``` <!-- --> --- ```r mean(et_xz) ``` ``` ## [1] 2.546074 ``` ```r mean(ot_xz) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.218902 ``` <!-- --> --- ```r cv = qt(p = .975, df = 100-3-1) esig = et_xz > cv sum(esig) ``` ``` ## [1] 66 ``` ```r osig = ot_xz > cv sum(osig) ``` ``` ## [1] 2 ``` In our simulation, 66% of experimental studies were statistically significant, whereas only 2% of observational studies were significant. Remember, we built our simulation based on data where there really is an interaction effect (i.e., the null is false). McClelland and Judd found that 74% of experimental studies and 9% of observational studies were significant. --- ### Efficiency <img src="images/efficiency.png" width="55%" /> ??? Efficiency = the ratio of the variance of XZ (controlling for X and Z) of a design to the best possible design (upper right corner). High efficiency is better; best efficiency is 1. --- ### Efficiency .pull-left[ If the optimal design has N obserations, then to have the same standard error (i.e., the same power), any other design needs to have N*(1/efficency). So a design with .06 efficency needs `\(\frac{1}{.06} = 16.67\)` times the sample size to detect the effect. ] .pull-right[  ] Coincidentally, this is the same ratio needed for [powering interactions compared to main effects](https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2018/03/15/need-16-times-sample-size-estimate-interaction-estimate-main-effect/). ??? This generalizes to higher-order interactions as well. If you have a three-way interaction, you need 16*16 (256 times the number of people). --- ## Observational studies: What NOT to do Recode X and Z into more extreme values (e.g., median splits). * While this increases variance in X and Z, it also increases measurement error. Collect a random sample and then only perform analyses on the subsample with extreme values * Reduces sample size and also generalizability. #### What can be done? M&J suggest oversampling extremes and using weighted and unweighted samples. --- ## Experimental studies: What NOT to do Forget about lack of external validity and generalizability. Ignore power when comparing interaction between covariate and experimental predictors (ANCOVA or multiple regression with categorical and continuous predictors). --- class: inverse ## Three-way interactions and beyond --- ### Three-way interactions (regression) .purple[Regression equation] `$$\hat{Y} = b_{0} + b_{1}X + b_{2}Z + b_{3}W + b_{4}XZ + b_{5}XW + b_{6}ZW + b_{7}XZW$$` The three-way interaction qualifies the three main effects (and any two-way interactions). Like a two-way interaction, the three-way interaction is a conditional effect. And it is symmetrical, meaning there are several equally correct ways of interpreting it. .purple[Factorial ANOVA] We describe the factorial ANOVA design by the number of levels of each factor. "X by Z by W" (e.g., 2 by 3 by 4, or 2x3x4) --- A two-way (A x B) interaction means that the magnitude of one main effect (e.g., A main effect) depends on levels of the other variable (B). But, it is equally correct to say that the magnitude of the B main effect depends on levels of A. In regression, we refer to these as .purple[conditional effects] and in ANOVA, they are called .purple[simple main effects.] A three-way interaction means that the magnitude of one two-way interaction (e.g., A x B) depends on levels of the remaining variable (C). It is equally correct to say that the magnitude of the A x C interaction depend on levels of B. Or, that the magnitude of the B x C interaction depends on levels of A. These are known as .purple[simple interaction effects]. --- ### Example (regression) ```r stress_data = read.csv(here::here("data/stress2.csv")) # necessary for simple_slopes() function later stress_data$class = as.factor(stress_data$class) #always check your data! psych::describe(stress_data, fast = T) ``` ``` ## Warning in FUN(newX[, i], ...): no non-missing arguments to min; returning Inf ``` ``` ## Warning in FUN(newX[, i], ...): no non-missing arguments to max; returning -Inf ``` ``` ## vars n mean sd min max range se ## X 1 150 75.50 43.45 1 150 149 3.55 ## class 2 150 NaN NA Inf -Inf -Inf NA ## bad_day 3 150 2.95 1.29 1 5 4 0.11 ## talk 4 150 2.57 1.20 1 5 4 0.10 ## stress 5 150 30.15 10.00 1 51 50 0.82 ``` ```r table(stress_data$class) ``` ``` ## ## freshman senior ## 83 67 ``` --- ```r mod_stress = lm(stress ~ bad_day*talk*class, data = stress_data) summary(mod_stress) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = stress ~ bad_day * talk * class, data = stress_data) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -10.6126 -3.2974 0.0671 3.1129 10.7774 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 20.2350 3.5643 5.677 0.0000000745 *** ## bad_day 2.4029 1.1284 2.129 0.0349 * ## talk 4.4668 1.8595 2.402 0.0176 * ## classsenior 0.1035 5.7548 0.018 0.9857 ## bad_day:talk 0.1041 0.5744 0.181 0.8565 ## bad_day:classsenior 0.1244 2.0069 0.062 0.9507 ## talk:classsenior -1.9797 2.2823 -0.867 0.3872 ## bad_day:talk:classsenior -1.5260 0.7336 -2.080 0.0393 * ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 4.733 on 142 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.7865, Adjusted R-squared: 0.776 ## F-statistic: 74.72 on 7 and 142 DF, p-value: < 0.00000000000000022 ``` --- ```r library(sjPlot) plot_model(mod_stress, type = "pred", terms = c("bad_day", # x-axis "talk[meansd]", # color of lines "class")) # facets ``` <!-- --> --- ```r library(emmeans) emtrends(mod_stress, var = "bad_day", ~class) ``` ``` ## class bad_day.trend SE df lower.CL upper.CL ## freshman 2.67 0.612 142 1.46 3.8790 ## senior -1.12 0.618 142 -2.34 0.0994 ## ## Confidence level used: 0.95 ``` --- ```r # choose levels of the moderator to test mylist = list(class = c("freshman", "senior"), talk = c(1.4, 2.6, 3.8)) emtrends(mod_stress, var = "bad_day", ~talk*class, at = mylist) ``` ``` ## talk class bad_day.trend SE df lower.CL upper.CL ## 1.4 freshman 2.549 0.494 142 1.572 3.5250 ## 2.6 freshman 2.673 0.625 142 1.437 3.9095 ## 3.8 freshman 2.798 1.220 142 0.387 5.2099 ## 1.4 senior 0.537 1.058 142 -1.556 2.6287 ## 2.6 senior -1.170 0.608 142 -2.371 0.0314 ## 3.8 senior -2.876 0.467 142 -3.800 -1.9527 ## ## Confidence level used: 0.95 ``` --- As a reminder, centering will change all but the highest-order terms in a model. ```r stress_c = stress_data %>% mutate( across( c(bad_day, talk) , ~.x-mean(.x) ) ) mod_c = lm(stress ~ bad_day*talk*class, data = stress_c) ``` --- ```r library(broom) tidy(mod_stress) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 8 × 5 ## term estimate std.error statistic p.value ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 (Intercept) 20.2 3.56 5.68 0.0000000745 ## 2 bad_day 2.40 1.13 2.13 0.0349 ## 3 talk 4.47 1.86 2.40 0.0176 ## 4 classsenior 0.104 5.75 0.0180 0.986 ## 5 bad_day:talk 0.104 0.574 0.181 0.856 ## 6 bad_day:classsenior 0.124 2.01 0.0620 0.951 ## 7 talk:classsenior -1.98 2.28 -0.867 0.387 ## 8 bad_day:talk:classsenior -1.53 0.734 -2.08 0.0393 ``` ```r tidy(mod_c) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 8 × 5 ## term estimate std.error statistic p.value ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 (Intercept) 39.6 0.702 56.4 4.45e-99 ## 2 bad_day 2.67 0.612 4.37 2.43e- 5 ## 3 talk 4.77 0.646 7.39 1.18e-11 ## 4 classsenior -16.2 1.10 -14.7 2.20e-30 ## 5 bad_day:talk 0.104 0.574 0.181 8.56e- 1 ## 6 bad_day:classsenior -3.79 0.870 -4.36 2.47e- 5 ## 7 talk:classsenior -6.49 0.882 -7.36 1.38e-11 ## 8 bad_day:talk:classsenior -1.53 0.734 -2.08 3.93e- 2 ``` --- ### Four-way? $$ `\begin{aligned} \hat{Y} &= b_0 + b_1X + b_{2}Z + b_{3}W + b_{4}Q + b_{5}XW\\ &+ b_{6}ZW + b_{7}XZ + b_{8}QX + b_{9}QZ + b_{10}QW\\ &+ b_{11}XZQ + b_{12}XZW + b_{13}XWQ + b_{14}ZWQ + b_{15}XZWQ\\ \end{aligned}` $$ -- 3-way (and higher) interactions are incredibly difficult to interpret, in part because they represent incredibly complex processes. If you have a solid theoretical rationale for conducting a 3-way interaction, be sure you've collected enough subjects to power your test (see above). --- Especially with small samples, three-way interactions may be the result of a few outliers skewing a regression line. If you have stumbled upon a three-way interaction during exploratory analyses, .purple[be careful.] This is far more likely to be a result of over-fitting than uncovering a true underlying process. Best practice for 3-way (and higher) interactions is to use at least one nominal moderator (ideally with only 2 levels), instead of all continuous moderators. This allows you to examine the 2-way interaction at each level of the nominal moderator. Even better if one of these moderators is experimenter manipulated, which increases the likelihood of balanced conditions. --- class: inverse ## Next time... Polynomials and bootstrapping