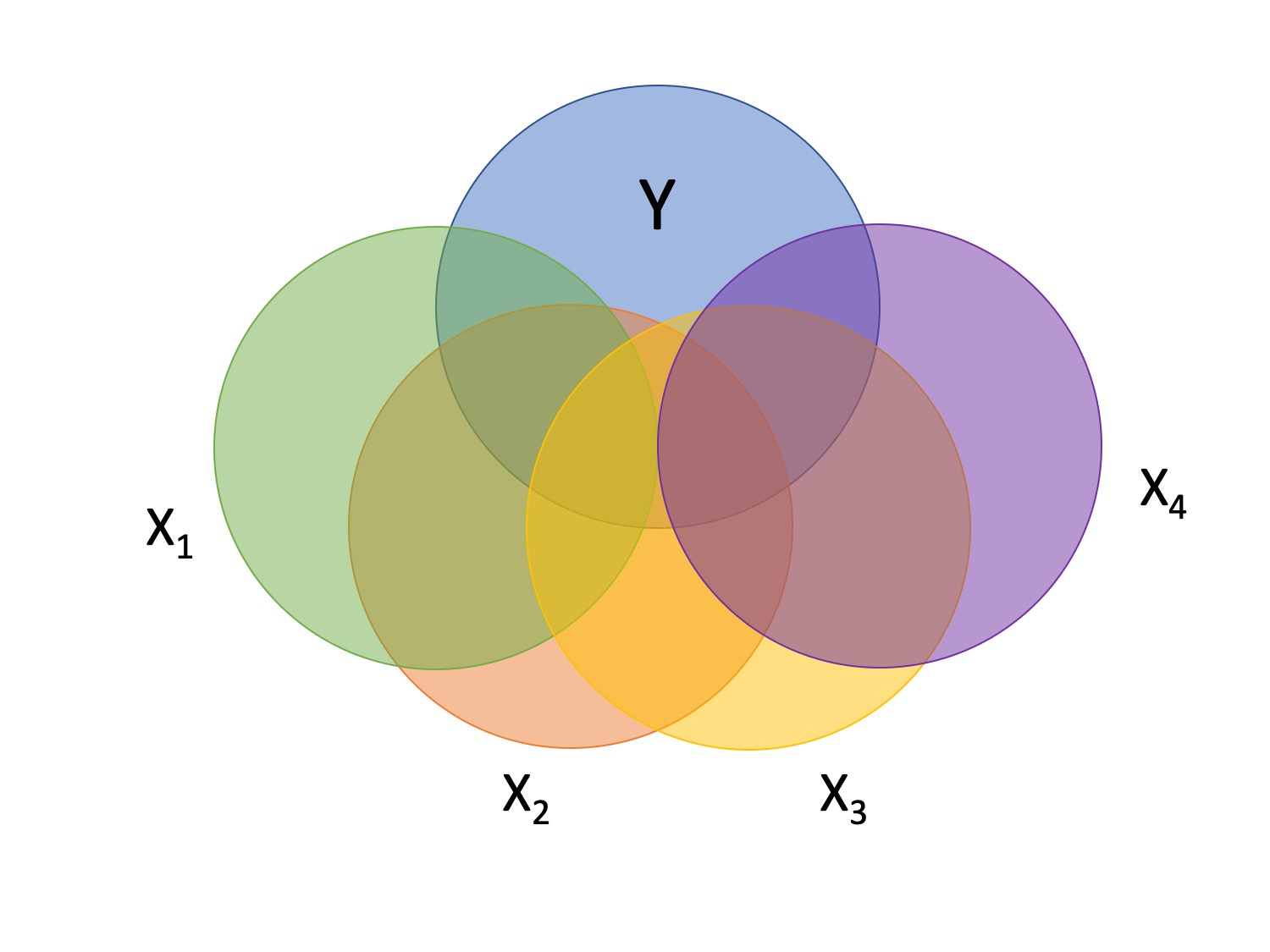

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Lecture 9: Multiple Regression II --- ## Some clarifications after HW1 * one- vs two-tailed tests * standard error of the estimate `\((s_{Y|X})\)` should be compared to original `\(s_Y\)` * Markdown formatting -- do not add `#` outside of code chunks --- ## Last time * Introduction to multiple regression * Interpreting coefficient estimates * Estimating model fit * Significance tests (omnibus and coefficients) --- ## Today * Tolerance * Hierarchical regression/model comparison * A note about the schedule --- ## Example from Thursday ```r library(here); library(tidyverse) support_df = read.csv(here("data/support.csv")) psych::describe(support_df, fast = T) ``` ``` ## vars n mean sd min max range se ## give_support 1 78 4.99 1.07 2.77 7.43 4.66 0.12 ## receive_support 2 78 7.88 0.85 5.81 9.68 3.87 0.10 ## relationship 3 78 5.85 0.86 3.27 7.97 4.70 0.10 ``` --- ```r mr.model <- lm(relationship ~ receive_support + give_support, data = support_df) summary(mr.model) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = relationship ~ receive_support + give_support, data = support_df) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -2.26837 -0.40225 0.07701 0.42147 1.76074 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 2.07212 0.81218 2.551 0.01277 * ## receive_support 0.37216 0.11078 3.359 0.00123 ** ## give_support 0.17063 0.08785 1.942 0.05586 . ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 0.7577 on 75 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.2416, Adjusted R-squared: 0.2214 ## F-statistic: 11.95 on 2 and 75 DF, p-value: 3.128e-05 ``` --- ## Standard error of regression coefficient In the case of univariate regression: `$$\Large se_{b} = \frac{s_{Y}}{s_{X}}{\sqrt{\frac {1-r_{xy}^2}{n-2}}}$$` In the case of multiple regression: `$$\Large se_{b} = \frac{s_{Y}}{s_{X}}{\sqrt{\frac {1-R_{Y\hat{Y}}^2}{n-p-1}}} \sqrt{\frac {1}{1-R_{i.jkl...p}^2}}$$` - As N increases... - As variance explained increases... --- `$$se_{b} = \frac{s_{Y}}{s_{X}}{\sqrt{\frac {1-R_{Y\hat{Y}}^2}{n-p-1}}} \sqrt{\frac {1}{1-R_{i.jkl...p}^2}}$$` ## Tolerance `$$1-R_{i.jkl...p}^2$$` - Proportion of `\(X_i\)` that does not overlap with other predictors. - Bounded by 0 and 1 - Large tolerance (little overlap) means standard error will be small. - what does this mean for including a lot of variables in your model? --- ## Tolerance in `R` ```r library(olsrr) ols_vif_tol(mr.model) ``` ``` ## Variables Tolerance VIF ## 1 receive_support 0.8450326 1.183386 ## 2 give_support 0.8450326 1.183386 ``` Why are tolerance values identical here? --- ## Suppression Normally our standardized partial regression coefficients fall between 0 and `\(r_{Y1}\)`. However, it is possible for `\(b^*_{Y1}\)` to be larger than `\(r_{Y1}\)`. We refer to this phenomenon as .purple[suppression.] * A non-significant `\(r_{Y1}\)` can become a significant `\(b^*_{Y1}\)` when additional variables are added to the model. * A *positive* `\(r_{Y1}\)` can become a *negative* and significant `\(b^*_{Y1}\)`. --- ```r stress_df = read.csv(here("data/stress.csv")) %>% dplyr::select(-id, -group) cor(stress_df) %>% round(2) ``` ``` ## Anxiety Stress Support ## Anxiety 1.00 -0.05 -0.55 ## Stress -0.05 1.00 0.52 ## Support -0.55 0.52 1.00 ``` --- ```r lm(Stress ~ Anxiety, data = stress_df) %>% summary ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = Stress ~ Anxiety, data = stress_df) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -4.580 -1.338 0.130 1.047 4.980 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 5.45532 0.56017 9.739 <2e-16 *** ## Anxiety -0.03616 0.06996 -0.517 0.606 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 1.882 on 116 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.002297, Adjusted R-squared: -0.006303 ## F-statistic: 0.2671 on 1 and 116 DF, p-value: 0.6063 ``` --- ```r lm(Stress ~ Anxiety + Support, data = stress_df) %>% summary ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = Stress ~ Anxiety + Support, data = stress_df) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -4.1958 -0.8994 -0.1370 0.9990 3.6995 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) -0.31587 0.85596 -0.369 0.712792 ## Anxiety 0.25609 0.06740 3.799 0.000234 *** ## Support 0.40618 0.05115 7.941 1.49e-12 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 1.519 on 115 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.3556, Adjusted R-squared: 0.3444 ## F-statistic: 31.73 on 2 and 115 DF, p-value: 1.062e-11 ``` --- ## Suppression Recall that the partial regression coefficient is calculated: `$$\large b^*_{Y1.2}=\frac{r_{Y1}-r_{Y2}r_{12}}{1-r^2_{12}}$$` -- Is suppression meaningful? ??? Imagine a scenario when X2 and Y are uncorrelated and X2 is correlated with X1. (Draw Venn diagram of this) Second part of numerator becomes 0 Bottom part gets smaller Bigger value --- ## Hierarchical regression/Model comparison ```r library(tidyverse) happy_d <- read_csv('http://static.lib.virginia.edu/statlab/materials/data/hierarchicalRegressionData.csv') happy_d$gender = ifelse(happy_d$gender == "Female", 1, 0) library(psych) describe(happy_d, fast = T) ``` ``` ## vars n mean sd min max range se ## happiness 1 100 4.46 1.56 1 9 8 0.16 ## age 2 100 25.37 1.97 20 30 10 0.20 ## gender 3 100 0.39 0.49 0 1 1 0.05 ## friends 4 100 6.94 2.63 1 14 13 0.26 ## pets 5 100 1.10 1.18 0 5 5 0.12 ``` --- ```r mr.model <- lm(happiness ~ age + gender + friends + pets, data = happy_d) summary(mr.model) ``` ``` ... ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 5.64273 1.93194 2.921 0.00436 ** ## age -0.11146 0.07309 -1.525 0.13057 ## gender 0.14267 0.31157 0.458 0.64806 ## friends 0.17134 0.05491 3.120 0.00239 ** ## pets 0.36391 0.13044 2.790 0.00637 ** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 1.427 on 95 degrees of freedom ... ``` ??? Review here: * Omnibus test * Coefficient of determination * Adjust R squared * Resid standard error * Coefficient estimates --- ## Methods for entering variables **Simultaneous**: Enter all of your IV's in a single model. `$$\large Y = b_0 + b_1X_1 + b_2X_2 + b_3X_3$$` - The benefits to using this method is that it reduces researcher degrees of freedom, is a more conservative test of any one coefficient, and often the most defensible action (unless you have specific theory guiding a hierarchical approach). --- ## Methods for entering variables **Hierarchically**: Build a sequence of models in which every successive model includes one more (or one fewer) IV than the previous. `$$\large Y = b_0 + e$$` `$$\large Y = b_0 + b_1X_1 + e$$` `$$\large Y = b_0 + b_1X_1 + b_2X_2 + e$$` `$$\large Y = b_0 + b_1X_1 + b_2X_2 + b_3X_3 + e$$` This is known as **hierarchical regression**. (Note that this is different from Hierarchical Linear Modelling or HLM [which is often called Multilevel Modeling or MLM].) Hierarchical regression is a subset of **model comparison** techniques. --- ## Hierarchical regression / Model Comparison **Model comparison:** Comparing how well two (or more) models fit the data in order to determine which model is better. If we're comparing nested models by incrementally adding or subtracting variables, this is known as hierarchical regression. - Multiple models are calculated - Each predictor (or set of predictors) is assessed in terms of what it adds (in terms of variance explained) at the time it is entered - Order is dependent on an _a priori_ hypothesis ---  --- ## R-square change - distributed as an F `$$F(p.new, N - 1 - p.all) = \frac {R_{m.2}^2- R_{m.1}^2} {1-R_{m.2}^2} (\frac {N-1-p.all}{p.new})$$` - can also be written in terms of SSresiduals --- ## Model comparison - The basic idea is asking how much variance remains unexplained in our model. This "left over" variance can be contrasted with an alternative model/hypothesis. We can ask does adding a new predictor variable help explain more variance or should we stick with a parsimonious model. - Every test of an omnibus model is implicitly a model comparisons, typically of your fitted model with the nil model (no slopes). This framework allows you to be more flexible and explicit. --- ```r fit.0 <- lm(happiness ~ 1, data = happy_d) summary(fit.0) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = happiness ~ 1, data = happy_d) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -3.46 -0.71 -0.46 0.54 4.54 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 4.460 0.156 28.59 <2e-16 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 1.56 on 99 degrees of freedom ``` --- ```r fit.1 <- lm(happiness ~ age, data = happy_d) summary(fit.1) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = happiness ~ age, data = happy_d) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -3.7615 -0.9479 -0.1890 0.7792 4.3657 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 7.68763 2.00570 3.833 0.000224 *** ## age -0.12722 0.07882 -1.614 0.109735 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 1.547 on 98 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.02589, Adjusted R-squared: 0.01595 ## F-statistic: 2.605 on 1 and 98 DF, p-value: 0.1097 ``` --- ```r anova(fit.0) ``` ``` ## Analysis of Variance Table ## ## Response: happiness ## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) ## Residuals 99 240.84 2.4327 ``` ```r anova(fit.1) ``` ``` ## Analysis of Variance Table ## ## Response: happiness ## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) ## age 1 6.236 6.2364 2.6051 0.1097 ## Residuals 98 234.604 2.3939 ``` ```r anova(fit.1, fit.0) ``` ``` ## Analysis of Variance Table ## ## Model 1: happiness ~ age ## Model 2: happiness ~ 1 ## Res.Df RSS Df Sum of Sq F Pr(>F) ## 1 98 234.60 ## 2 99 240.84 -1 -6.2364 2.6051 0.1097 ``` --- ## Model Comparisons - This example of model comparisons is redundant with nil/null hypotheses and coefficient tests of slopes in univariate regression. - Let's expand this to the multiple regression case model. --- ## Model comparisons ```r m.2 <- lm(happiness ~ age + gender, data = happy_d) m.3 <- lm(happiness ~ age + gender + pets, data = happy_d) m.4 <- lm(happiness ~ age + gender + friends + pets, data = happy_d) anova(m.2, m.3, m.4) ``` ``` ... ## Analysis of Variance Table ## ## Model 1: happiness ~ age + gender ## Model 2: happiness ~ age + gender + pets ## Model 3: happiness ~ age + gender + friends + pets ## Res.Df RSS Df Sum of Sq F Pr(>F) ## 1 97 233.97 ## 2 96 213.25 1 20.721 10.1769 0.001927 ** ## 3 95 193.42 1 19.821 9.7352 0.002394 ** ... ``` ```r coef(summary(m.4)) ``` ``` ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 5.6427256 1.93193747 2.9207599 0.004361745 ## age -0.1114606 0.07308612 -1.5250586 0.130566815 ## gender 0.1426730 0.31156820 0.4579192 0.648056200 ## friends 0.1713379 0.05491363 3.1201349 0.002394079 ## pets 0.3639113 0.13044467 2.7897749 0.006373887 ``` --- ### change in `\(R^2\)` ```r summary(m.2)$r.squared ``` ``` ## [1] 0.02854509 ``` ```r summary(m.3)$r.squared ``` ``` ## [1] 0.1145794 ``` ```r summary(m.4)$r.squared ``` ``` ## [1] 0.1968801 ``` --- ## partitioning the variance - It doesn't make sense to ask how much variance a variable explains (unless you qualify the association) `$$R_{Y.1234...p}^2 = r_{Y1}^2 + r_{Y(2.1)}^2 + r_{Y(3.21)}^2 + r_{Y(4.321)}^2 + ...$$` - In other words: order matters! --- What if we compare the first (2 predictors) and last model (4 predictors)? ```r anova(m.2, m.4) ``` ``` ## Analysis of Variance Table ## ## Model 1: happiness ~ age + gender ## Model 2: happiness ~ age + gender + friends + pets ## Res.Df RSS Df Sum of Sq F Pr(>F) ## 1 97 233.97 ## 2 95 193.42 2 40.542 9.9561 0.0001187 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ``` --- Model comparison can thus be very useful for testing the explained variance attributable to a .purple[set] of predictors, not just one. For example, if we're interested in explaining variance in cognitive decline, perhaps we build a model comparison testing: * Set 1: Demographic variables (age, gender, education, income) * Set 2: Physical health (exercise, chronic illness, smoking, flossing) * Set 3: Social factors (relationship quality, social network size) --- class: inverse ## Next time... Categorical predictors, AKA Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)